Remembering the Parents Who Shaped Willie Mays

Willie Mays, the Hall of Fame baseball player who electrified the game and stunned fans with his sterling defense and explosive hitting power, died on Tuesday at the age of 93.

When asked for the secret to his success, he once replied, “They throw the ball, I hit it. They hit the ball, I catch it. It’s simple.”

Understated and graceful, Mays endeared himself to fans at a time when black players in the Major Leagues were still considered controversial, at least to some.

Mays’ statistics speak for themselves: 3,293 hits, 660 home runs – and 12 Gold Glove awards.

“Willie Mays is the closest to being perfect I’ve ever seen,” said the Yankees’ legend, Joe DiMaggio.

Only life off the field hadn’t always been so ideal.

Born to unmarried parents outside of Birmingham, Alabama in 1931, Willie’s mother was just 16 when he came into the world. She abandoned him as a baby, left and married another man – and then had 10 other children. Just five miles from Willie, who was being raised by his father, Annie Satterwhite dipped in and out of his life. She died when Willie was 21.

Willie’s father, William, was nicknamed “Cat” for his graceful movements in the outfield, where he played semi-pro ball for a local industrial league. The Hall of Famer credited his father with instilling in him a resilience that would pay great dividends.

“My father gave me that one thing, positive thinking, that allowed me to look past whatever was happening,” Mays said. “If you say to me, well, ‘there had to have been some pain,’ sure there was some pain. But if you can overcome your pain and do your job, the pain disappears the next day. That’s where the positive thinking comes in.”

Still, biographer James Hirsch, who wrote, Willie Mays: The Life, The Legend, said the early loss of his mother and the general unevenness of his childhood made the star player suspicious of others.

“The root of his trust issues is that he feels he was betrayed in many different ways over the years, taken advantage of financially, he had a rather unfortunate first marriage that ended badly and he was the subject of racial discrimination,” Hirsch said. “But the thing about Willie, he will never complain about those kinds of misfortunes.”

Hirsch continued:

“Willie was taught growing up in Alabama that if you are a black person and you want to survive in the white world, you keep your mouth shut and you keep your head down,” said Hirsch. “Willie said, ‘That’s how I was programmed.’ But that doesn’t mean he wasn’t hurt by these betrayals, he just internalized all of those. The effect of that, he is very wary of people who come up to him. When you are Willie Mays, everybody wants something from you. There just came a point in Willie’s life where he said, ‘I don’t think I can trust anyone.’”

As Hirsch alluded to, Mays married Margherite Wendell Chapman in 1956, and they adopted a baby boy in 1959.

“She and I were to go to an adoption agency, and that is how my son Michael came to live with us,” Willie once recalled. “He was three days old when we adopted him. I don’t know what the chemistry was, but from the first moment I set eyes on him, I knew this was it. And it’s been that way ever since… All I can say is, he changed my life, my purpose, my outlook.”

Sadly, Willie and Margherite divorced in 1963. Remarrying in 1971 to Mae Louise Allen, Mays’ union lasted until his wife’s death in 2013. Their 42-year marriage included Willie caring for Mae for the last 16 years of her life as she suffered from Alzheimer’s.

Intensely private, Willie stayed out of the spotlight in his later years. A business relationship with a casino caused some controversy with Major League Baseball following his retirement from the game, but that was eventually resolved.

Over the years, Willie spoke lovingly of both of his parents. He had sympathy for his mother, but it was his father who obviously influenced him the most.

Knowing his son was to face the challenges of integration in baseball, the elder Mays advised Willie, “Just tell the truth and be true to yourself, and you can go on.”

In turn, the father knew the son. Talking with his first coach out of high school, “Cat” Mays told him:

“Don’t holler at him [Willie],” he said. “If you want something done, tell him and he’ll do it, but if you holler, he’s going to back up, and you’re not going to get anything out of him.”

The baseball world will rightly laud and grieve Mays’ passing, but his life demonstrates once more the significant and critical influence of a mother and father, for good and bad.

Image from Getty.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Paul J. Batura is a writer and vice president of communications for Focus on the Family. He’s authored numerous books including “Chosen for Greatness: How Adoption Changes the World,” “Good Day! The Paul Harvey Story” and “Mentored by the King: Arnold Palmer's Success Lessons for Golf, Business, and Life.” Paul can be reached via email: Paul.Batura@fotf.org or Twitter @PaulBatura

Related Posts

New Research Shows How Fatherhood Uniquely Boosts Child Health

February 10, 2026

Why Adoption is Beautiful and Surrogacy Isn’t

February 6, 2026

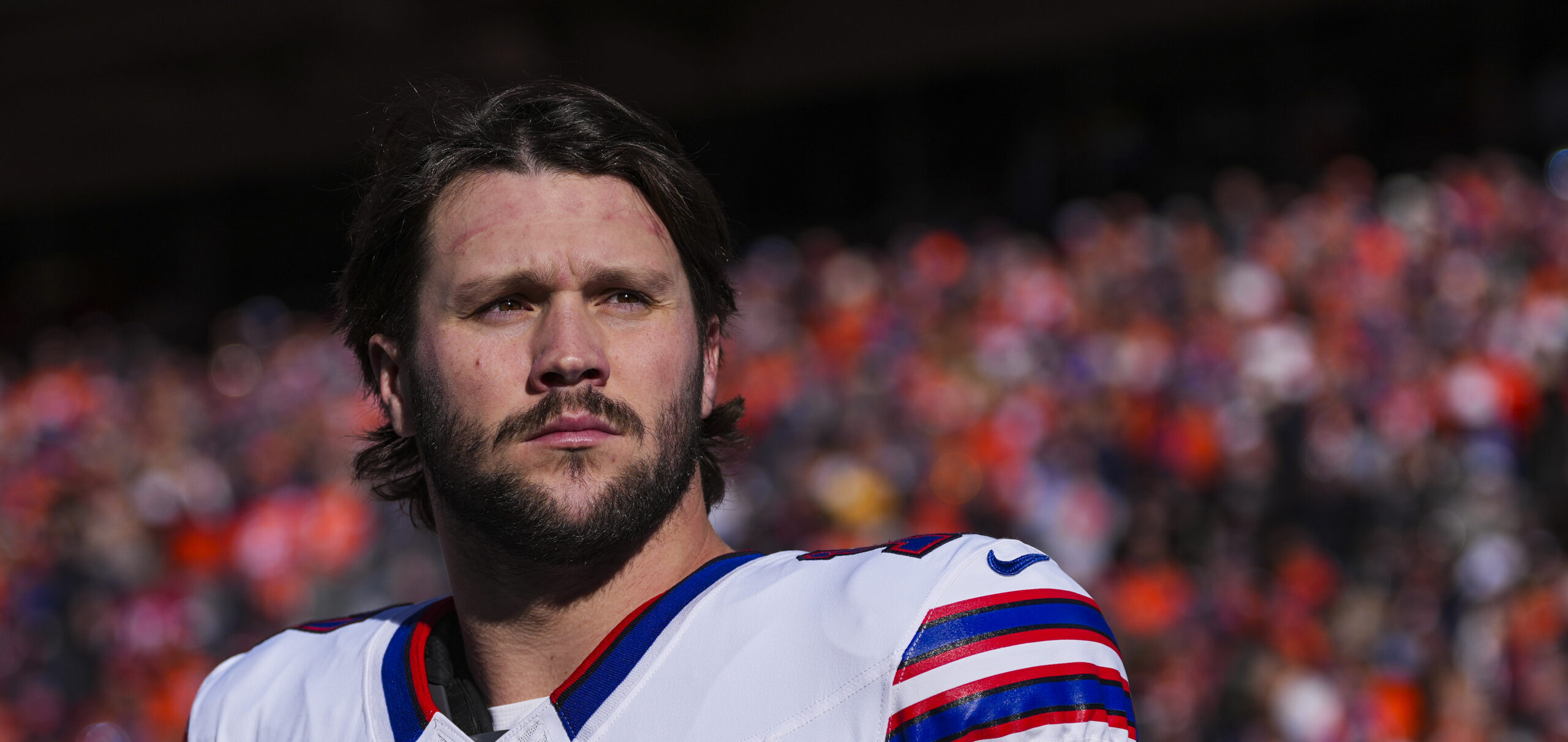

Josh Allen: Being a Dad is ‘Most Important Thing’

January 30, 2026