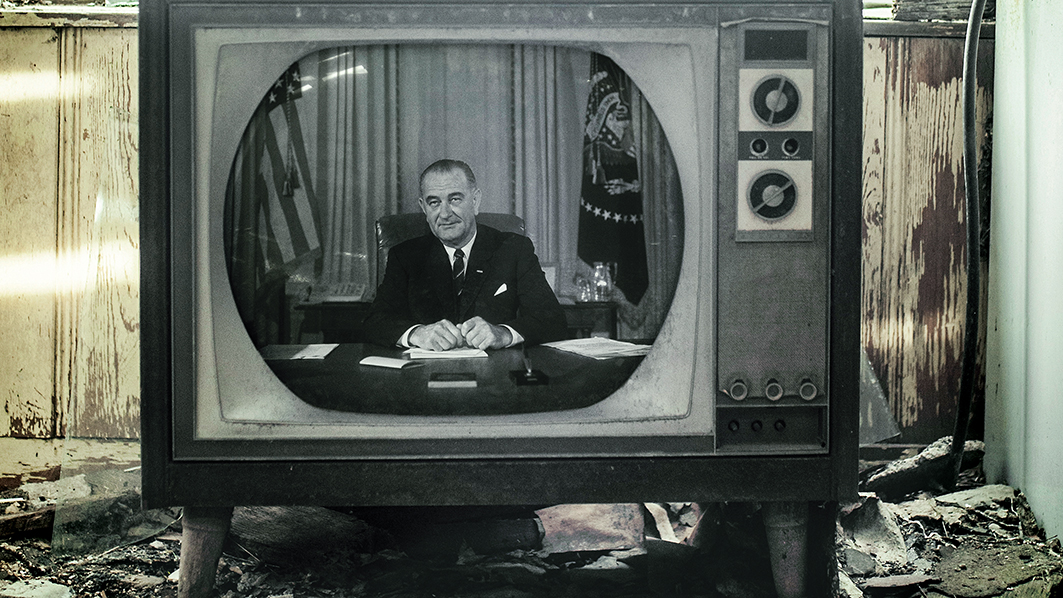

In 1966, there was a major revolution in American government that would have a massive impact on millions of families and marriages. It can all be traced back to one particular U.S. president and the unique circumstances that brought him to the Oval Office.

The story has been lionized in popular culture. But a half century later, it is worth asking whether the celebratory tone of it all is really an accurate reflection of what that revolution’s impact has actually been.

Johnson’s massive domestic agenda was taken from a now-forgotten British professor named Graham Wallas, who in 1914 outlined a series of domestic reforms he called “The Great Society.” Wallas’ proposals have faded with time, but the slogan he coined entered the American lexicon as one of the most famous names in politics and inseparable from Johnson’s legacy.

In 1964, Johnson went to the University of Michigan to deliver one of the most consequential speeches of his young presidency, unveiling the Great Society programs which would become the largest, most intrusive expansion of the federal government ever.

“The challenge of the next half-century is whether we have the wisdom to use wealth to enrich and elevate our national life, and to advance the quality of our American civilization,” he said in soaring tones. “For in your time we have the opportunity to move not only toward the rich society and the powerful society, but upward to the Great Society.”

“Upward” was the operative word.

The gigantism of the Great Society made President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal of the 1930s, and the progressive-era initiatives of presidents Woodrow Wilson and Theodore Roosevelt, appear relatively modest by comparison.

The revolution Johnson launched that day in Ann Arbor was the most far-reaching legislative transformation of our nation.

How did it actually happen? And is his legacy—especially its impact on the most vulnerable American families and marriages—worth celebrating in popular culture?

True Greatness

Johnson and his staff lost no time after Kennedy’s assassination, beavering away around the clock to design a series of new programs that would be financed by America’s post-World War II abundance. “I am a Roosevelt New Dealer,” Johnson said the day he took office. “Kennedy was a little too conservative to suit my taste.”

At the time, Americans overwhelmingly trusted the federal government to expand outward, upward and across the continent. The war had given them outsized confidence in what Washington could achieve on a grandiose scale. The Johnson administration leveraged that confidence by radically altering the constitutional limits on legislation, regulation and spending.

The Johnson administration shifted the governance of the country from a constitutional republic rooted in localism to an opaque, vast regulatory state rooted inside the beltway. The sheer size and scope of government would grow exponentially as a result.

What the president outlined was a cornucopia of new programs and funding mechanisms that would seamlessly seep into almost every facet of life and with a special emphasis on urban America. Never before had the government deigned it its solemn right and obligation to so deeply inject itself into the lives of older Americans; into the education system at every level; and perhaps most importantly, into the lives and personal decisions of the most vulnerable families in the country.

The relationship between the average citizen and the national government was altered forever.

Great Undertaking

Johnson cast his vision of the Great Society with strong bipartisan support.

The promises emanating from the nation’s capital were sometimes almost mystical: Cities large and small would be built and rebuilt with the federal government as the grand marshal of the funding parade. Poverty would be eradicated altogether. Racial discrimination would be sent to the ash heap of history. Public schools would be gleaming and bright. Families would feel unprecedented stability because Uncle Sam was going to be the new center of their strength and future. The promises seemed endless.

Ironically, liberal Democrats expressed the most initial misgivings about Johnson’s vision and pledges. But they soon climbed aboard what quickly became a proverbial gravy train of federal spending built upon the central promise of the Great Society: If the government didn’t expand, the country would fall into chaos, especially in the urban core where racial tension had been building since the late 1950s.

Great Goals

As Robert Caro and Randall Woods have made crystalline in their definitive histories of the Johnson era, the president intimidated feckless members of Congress into supporting the new federal leviathan he was systematically creating. Johnson knew how the game on Capitol Hill was played because he had become its legendary master during a long tenure as one of the most powerful majority leaders in Senate history. Members of Congress buckled under to Johnson’s seemingly endless demands and deals.

That year, 1964, will be remembered as one of the most eventful for new legislation ever. It was propelled by the sheer political dynamism of Johnson’s personality and outsized ambition.

It all began with the Economic Opportunity Act, which created Johnson’s “war on poverty” matrix of programs. It was swiftly passed and signed into law. So were the Civil Rights Act and a major tax cut that had been one of Kennedy’s main economic goals. Even before the tax cut became law, America was experiencing a remarkable boom in the economy, growing at 6 percent in the years between 1963 and 1966.

That kind of sustained economic growth was catnip to the creators of the modern administrative state, because their new government programs could enjoy a large, steady funding stream. Taxpayer dollars would flow into Washington coffers as never before.

Johnson sailed into victory over Arizona Sen. Barry Goldwater in the ’64 presidential race, winning an astonishing 61 percent of the vote, surpassing even his political hero Franklin Roosevelt’s highest vote totals. Johnson’s landslide allowed the Democratic Party to dominate both the House and Senate, creating a political lever of new votes to pass many more of Johnson’s legislative initiatives, including the most far-reaching education bill ever.

A beaming Johnson signed into law both the Elementary and Secondary Education Act and the Higher Education Act, federalizing public and private education in a manner simply unthinkable in the American experience until that time.

Following those victories, Johnson and his team were the architects of two new massive entitlement programs that would provide health care for older Americans and for the poor, Medicare and Medicaid. Never before had there existed a permanent, immovable role for Washington in Americans’ health care coverage.

Medicare had about 20 million people enrolled by 1966; there are 60 million today, and there will be 80 million in the next 20 years. Medicaid began with 4 million beneficiaries; today, it has 70 million.

Johnson didn’t stop there. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 followed, as did the Immigration and Nationality Act which for the first time removed the preference for immigrants from Europe and put into place new safeguards favoring immigrants from Latin America, Africa and Asia. The goal was to change the ethnic composition of America.

On and on these new gargantuan programs and departments flowed into existence—food stamps, arts and humanities agencies, environmental edicts, a Department of Transportation and a Department of Housing and Urban Development, to name but a few. The modern welfare state was launched in the first six months of Johnson’s presidency. It was bewildering.

Great Problems

What was becoming obvious after this blizzard of new legislation was that most of the funding projections for how much the Great Society would actually cost were not only wrong but wildly inaccurate. A half-century later, we know that the Great Society cost American taxpayers a staggering $22 trillion. The annual cost of the entitlements alone, when coupled with Social Security and Obamacare, helped contribute to a national debt surpassing $20 trillion and growing.

Fifty years after most of the Great Society programs were cemented into place, it’s almost impossible to measure the damage they inflicted on the most vulnerable marriages and families in the United States. This is perhaps the most dismal legacy of the Johnson years, and a sad testament to the vision of social planners who believed more government would mean stronger families and marriages.

In the spring of 1965, a sociologist working in the Labor Department, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, who would later serve in the U.S. Senate and become an advisor to presidents of both parties, shared with Johnson and his team a report he had compiled on the condition of black families in America.

Moynihan concluded that poverty and urban stress were contributing to the fracturing of families, resulting in 25 percent of all black children being born illegitimately. Moynihan called it a crisis.

Johnson used Moynihan’s study as an important part of a speech he delivered at Howard University in Washington, D.C., that year, suggesting that among the solutions to the problems of poor black families should be a guaranteed, government-provided income. Johnson and his policy team were convinced that expanding government funding for broken families would help save them.

Instead, by incentivizing government funding of single mothers who did not marry the fathers of their children, and by expanding the panoply of welfare state programs to Americans who were already experiencing serious stress and hardship, a series of significant problems became a tangle of pathologies.

Millions of Americans were soon engulfed in chaos and dysfunction. Major metropolitan areas were comprised of block upon block of victimized children, broken families and shattered lives.

A plague of fatherlessness ensued, leading to nearly 72 percent of all American black children being born without married parents by 2015. Marriage has become a rare and distant thing.

Did it have to be this way? When Johnson came to office in late 1963, more than 90 percent of all American babies had married parents. The 1960 census showed that nearly nine of every 10 children from birth to 18 years of age lived with two married parents.

In fact, between 1940 and 1965, illegitimacy had grown from 4 percent to 8 percent, but in the next 25 years, those numbers would dramatically jump to nearly 30 percent.

Today, more than 40 percent of all Americans are born to unmarried mothers. More than three of every 10 children live in some arrangement other than a two-parent home. Cohabitation continues to climb, and has become the acceptable norm for millions of Americans. The most recent Census Bureau report says barely half of all American children are living with both married biological parents.

Marriage rejection rooted in the 1960s has real ramifications: Today, 46 percent of adults up to 34 years of age have never been married.

Great Scot!

The Great Society produced a miserable society in some of America’s most difficult neighborhoods while the nuclear family became entangled by a federal government too often engineered by unaccountable bureaucrats. Unparalleled family breakdown in America’s toughest neighborhoods is, in part, the sad result of Lyndon Johnson’s miscalculations and unworkable solutions.

We are living through the collapse of marriage and the traditional family as not only the norm, but also the expectation, for millions of Americans, especially in low-income communities.

Writer Myron Magnet observed that the “dream” of the Great Society has in reality become a “nightmare” for the very people the Great Society was designed to help. Poverty and single-mother households were both higher after the Great Society than before, and the number of intact families experienced significant decline.

President Ronald Reagan, who was governor of California during the Johnson years, observed: “In the ‘60s, we waged a war on poverty, and poverty won.”

In a major analysis of Johnson’s war on poverty, the sociologist Nicholas Eberstadt of the American Enterprise Institute concluded: “The official poverty picture looks even worse the more closely one focuses on it … the poverty rate for all families was no lower in 2012 than in 1966. The poverty rate for American children under 18 is now higher than it was then. The poverty rate for the working-age population (18-64) is also higher now than back then. The poverty rate for whites is higher now than it was back then. Poverty rates for Hispanic Americans … likewise are higher today than back then.”

The consequences of broken families and widespread poverty are profound. Reliable sociologists and demographers, liberal and conservative alike, concur that children from broken family structures are far more likely to become involved in crime as intergenerational dependence on government grows.

Writes Eberstadt: “Since the launch of the War on Poverty, criminality in America has taken an unprecedented upward turn within our nation. Although reported rates of crime victimization—including murder and other violent crimes—have been falling for two decades, the percentage of Americans behind bars has continued to rise … As of year-end 2010, more than 5 percent of all black men in their 40s and nearly 7 percent of those in their 30s were in state or federal prisons …”

William Simon Foundation President James Piereson, who has studied urban issues for decades and cogently analyzed the 1960s, has concluded: “The scores of burned-out, crime-ridden, and bankrupt cities in America today must be counted as part of the legacy of the Great Society.”

Originally published in the October 2016 issue of Citizen magazine.