Babies are important for many reasons. Not least of which, they are the future. Literally.

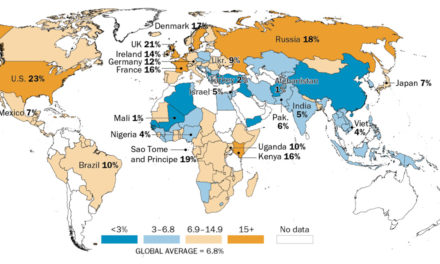

Unfortunately, every developed nation in the world, and too many underdeveloped nations, are not having the babies needed to simply replace their present population, much less see essential, healthy growth. This is a very serious problem.

Compelling women to have more babies than they desire is an ethical problem. But let us not assume this underpopulation is necessarily a problem of desire.

We must ask these obvious questions: Are women having all the babies they desire? Or are they just not wanting enough babies to replenish the human population?

These are important questions because helping women accomplish their most important life goals is critical to life satisfaction. And nearly every mom will tell you at length that their babies easily rank at the top of the most important parts of their lives.

So how many babies do women actually desire and how many are they actually having?

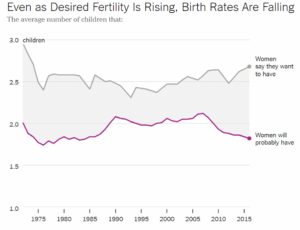

Demographer Lyman Stone wrote in The New York Times some years ago that this gap is “far short of what women themselves say they want for their family size.” Women generally report that they would like to have an average of 2.7 children, while in reality they will only have 1.8 on average. Men report essentially the same ideal fertility rate as women. Stone demonstrates this stark gap in the chart below.

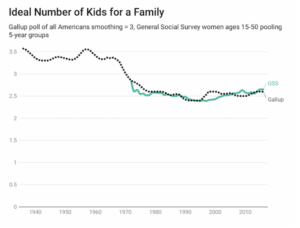

So declining fertility is not because women just don’t want more children. They do, and their actual stated desire is above replacement level, which is good. And while their desire for children has been declining to be sure, it is dropping much more moderately than their actual fertility, as shown in the following two charts.

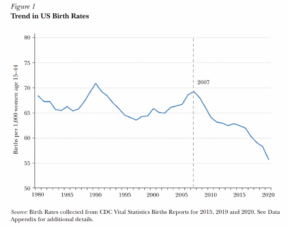

Compare this with our nation’s steep birthrate drop.

So why the significant gap between the number of babies women in child-bearing years desire and how many babies they actually have?

In 2018, The New York Times asked women their reasons for having fewer babies and financial issues were among their top reasons.

But a more recent academic study conducted by leading economists and published in the Journal of Economic Perspectives could not find a tight economic reason for declining birth rates for women. These scholars explain, “We are unable to identify a strong link between any specific policies or economic factors and the declining birth rates.” (emphasis added)

Lyman Stone, research fellow at the Institute for Family Studies, just published a new article in The Atlantic that seems to challenge the “children are too expensive” excuse based on two new economic studies on the life changes of lottery winners in Sweden and the United States. Lottery winning men are indeed more likely to get married and have more children, with an increase in new fatherhood by about 13 percent. Women who become big winners, not so much. The big change for women who win the lottery is divorce, with their rate doubling in the first few years after striking it rich. And divorced women don’t tend to have their minds on having more babies. Thus, the Atlantic admits, “one of the most popular explanations for declining fertility [supposed expense of children] may be wrong.”

The scholars writing in the Journal of Economics Perspectives also failed to find a link between declining fertility and falling adherence to religion, stating, “Again, despite the national trend [in declining religiosity], we see no evidence that states where religiosity declined the most experienced a greater relative decline in birth rates.”

This research team adds that declining fertility in the United States does not fit other traditional liberal explanations either. They directly state the facts “[do] not fit with the narrative that if the United States had more supportive government programs – such as subsidized childcare and generous paid work leave – its birth rates would be higher.”

They conclude,

Still, the international comparisons combined with the difficulty of finding policy and economic factors to explain the sustained decline in US birth rates suggest that these factors are not driving the changes in US birth rates. [emphasis added]

So, none of the usual explanations offered by elite influencers for declining birth rates proved tenable to these scholars. What do they believe is driving the gap between the number of babies women desire and how many they actually have?

They explain that it is more a factor of personal values, specifically asserting that “perhaps the key explanation for the post-2007 sustained decline in US birth rates is not about some changing policy or cost factor, but rather shifting priorities across cohorts of young adults.”

So yes, there is a significant gap between the number of children women say they would like to have and that which they actually have. But it seems to be more a battle between perceived values and possible conflicting life goals. Single-cause explanations like affordability do not seem to be supported by a diversity of academic data.

However, one thing is clear. We should, and must, do what we can to help women today achieve their desired fertility because babies are a rich source of personal happiness and the road to our future. Under current rates, that future does not look too good.

Women’s desire for more children is a critical solution and worth celebrating and encouraging.

Photo from Shutterstock.