Pitchers and catchers began arriving at Major League Baseball camps in Florida and Arizona this week, an annual tradition that marks the unofficial beginning of spring.

I grew up in a baseball town, a small company-owned town in southwestern Virginia that felt similar to the fictional Mayberry from the old “Andy Griffith” television show.

The entire local economy revolved around textiles. Almost everyone in town worked at the cotton mill and, each week, a train came to town with the cotton and left with the cloth.

We loved baseball not unlike the country as a whole during the ‘20s, ‘30s and ‘40s. Our warm weather calendar revolved around the sport, and we had the premier ballpark in our part of the state.

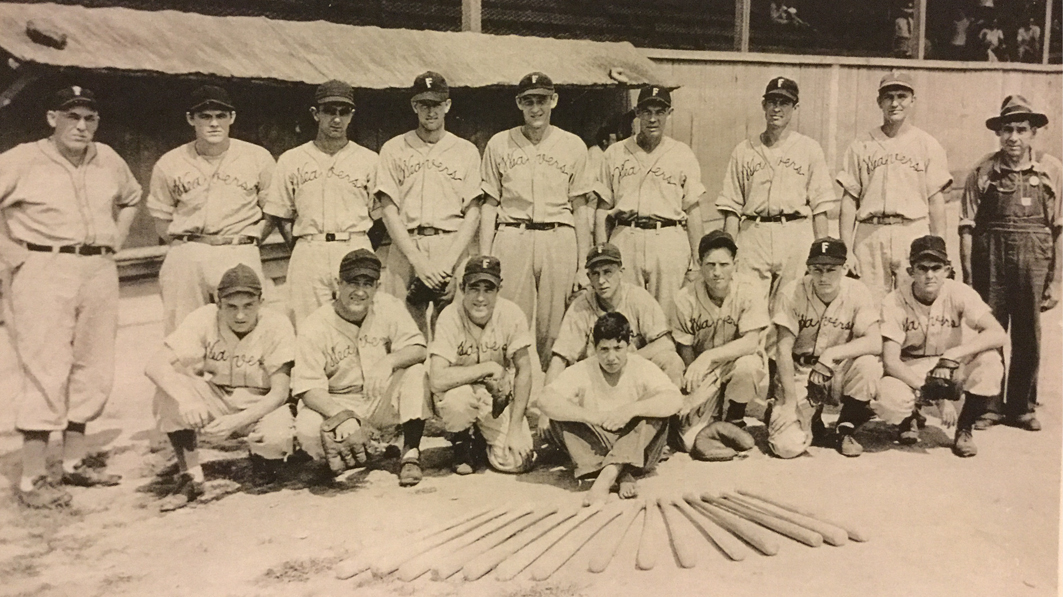

Teams practiced and played games almost round the clock, including under lights hoisted on telephone poles, cut from what must have been the tallest trees I’d have ever seen. My dad (last on bottom right) played for the “Weavers,” a name taken from one of the most well-known processes that involved weaving cloth.

Our tiny hamlet even produced two major league players, one who went on to manage a World Series championship team and the other who played in a World Series.

Growing up in the 1960s, I learned an early lesson about life during my many hours at the ballpark.

When I was around age 5, Dad took me to the ballpark for the first time to watch my brother play high school ball. As we walked into the grandstand, a creaky, wooden structure built not long after the turn of the century, I noticed a crude two-by-four railing behind the visitor dugout. It separated about 10 percent of the seats from the rest.

I asked what the divider was for and Dad explained, in 1960s terminology: “That’s where the ‘colored’ people used to have to sit back in the old days.”

Even at a very young age, I was impacted. “Why would they have to sit away from everyone else?” I wondered. That was the first time I recall encountering racism.

Surely we Americans have come a long way — in practice and in terminology — since my first visit to our formerly segregated grandstand.

But we have a long way to go.

Separate seating, schools and other things are now on the ash heap of history, but racism is far from dead. Even in my own home state, the current governor is being called to resign over racist actions in his past and comments he has made recently.

I saw prejudice from another side in 1988 when I was personal aide to the first African-American candidate for a federal statewide office in Virginia. A good man and a former minister who marched with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., he experienced rejection from voters of his own race. Why? Because he was running as a Republican.

He always had to be careful about perceptions. At one late-night meeting with black community leaders in Richmond, he had me wait in the car. “I cannot bring a white guy into this meeting,” he said. Was I offended? Not at all. But I still remember it, some 30 years later.

Racism is also far from localized.

Racial stereotypes seem to be cast upon the Southern states, harkening back to the Civil War of course, and to the Jim Crow era which followed. But anyone assuming racism in America is just a Southern thing is greatly mistaken. Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas wrote in his autobiography that he experienced far more racism when he attended school at Yale, in Connecticut, than he ever did growing up in Georgia

We must reach out and begin to understand each other in America. Politicians who seek laws regarding voting integrity, for instance, while needed, must understand that evokes painful memories among African-Americans, who long faced voter discrimination, even after the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

Those who call for English-only laws should understand that Hispanic-Americans want their children to speak English. However, much of the rhetoric used in those discussions is insulting to their parents or grandparents who can speak only Spanish.

Progressives who push for wider immigration and open borders must understand that during America’s best days, it was the concept of the melting pot which made our country such a success, not our current trend toward Balkanization.

Dr. King often said that 11:00 on Sunday morning was the most segregated hour of the week. That was in the 1960s. But it is not that different today in many parts of the country. As Christians, we must understand that God is no respecter of persons and that heaven will be marvelously multi-colored.

Racism is a national ill that undermines individuals and communities, and we Christians must lead the way toward true racial harmony. We must recognize that every person is made in the image of God.

Another lesson from my very early childhood, in fact, my mother’s first lesson to me, was that no one should think himself superior to any other. Those are good words to live by.

Joel D. Vaughan is the chief of staff for Focus on the Family.