It’s just past noon on a spring afternoon in 1930. The location is Bill’s Place, a popular diner directly across the street from South High School in Grand Rapids, Mich. Most of the lunch crowd has been served and are now settled in their seats. A cacophony of steady conversation fills the room.

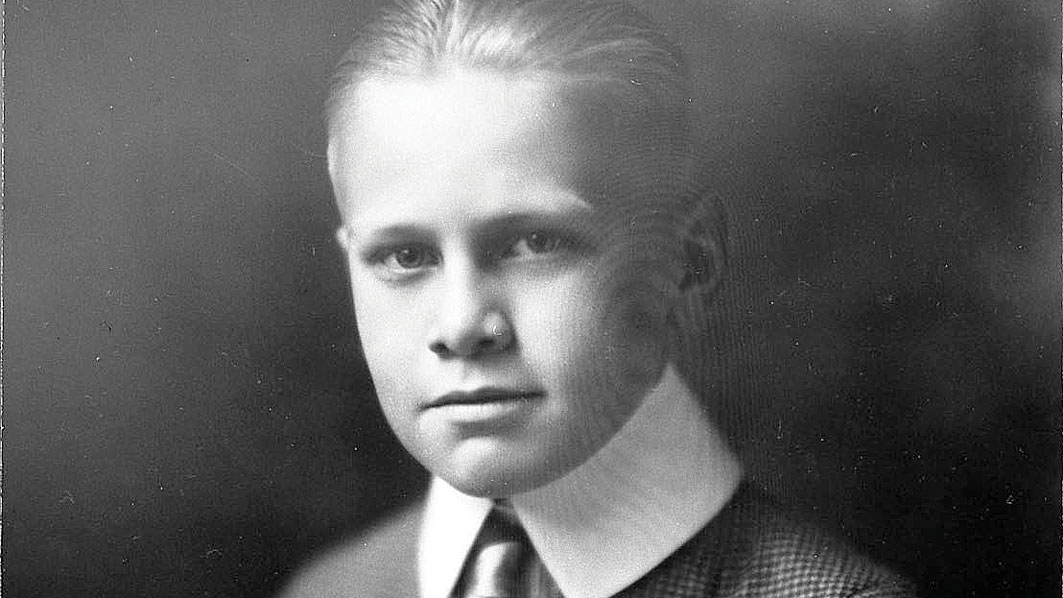

Several young, apron-clad servers are hustling between the tables and the kitchen, carrying plates of food, filling and refilling water glasses and coffee cups. Behind the counter is 17-year-old Gerald Ford, a junior at South High. Jerry, as he’s known to his friends, is handsome and well-liked, the captain of the football team.

During a lull in the action at the diner, Ford looks up to notice a tall, well-dressed man standing alone by the door. He’s not looking to be seated. He’s just standing—and staring.

Ford carries on with his duties and looks up again to find the gentleman studying him. It makes him uneasy. Finally, the man

walks from the door to the counter and directly up to Ford.

“Are you Leslie King?” the man asks Jerry.

“No,” Ford replies.

“Are you Jerry Ford?” he then asks.

“Yes,” answers the young man, a perplexed look washing across his face.

“You’re Leslie King. I’m your father. You don’t know me. I’m in town with my wife, and I would like to take you out for lunch.”

Initial Infatuation

Leslie King first met Gerald Ford’s mother, Dorothy Gardner, while visiting his sister at Knox College in Illinois in 1912. According to those who knew them, it was love at first sight. King impressed the attractive brunette with his dreams and plans for the future. He was a man ready to rise and eager to build a life with his new love.

In 1900, the King family’s wealth was estimated to be approximately $10 million, or nearly $250 million in today’s currency. Leslie’s father was Charles Henry King, an Omaha businessman who amassed his fortune in conjunction with the expansion of the transcontinental railroad. Various business interests, including the Omaha Wool and Storage Company, led King to also help establish several cities in Nebraska and Wyoming.

Convinced he and Dorothy were meant for one

another, Leslie wrote her father, Levi Gardner, asking his permission to marry her. Though not nearly as wealthy as the Kings, the Gardners were a prominent family in Harvard, Ill. Gardner had been the town’s mayor and owned a successful furniture store and real estate business. His wife, Adele, hailed from the family that founded the town.

Loving and protective parents, the Gardners wanted to know more about Leslie. Did he have the means to care for Dorothy? He assured them he had considerable savings ($35,000) and earned $150 a month working at the family’s wool business. The parents enthusiastically gave their blessing.

The wedding, on Sept. 17, 1912, was the talk of Harvard. “Many Harvard people met the young Omaha man who has won one of the most popular of Harvard young ladies as his bride,” reported the Harvard Herald. “He is a young man of good repute and is a highly regarded business man.”

Sadly, neither claim was actually true.

Rage and Abuse

Just 10 days after the wedding, while on their honeymoon at the Multnomah Hotel in Portland, Ore., Leslie struck Dorothy for the first time—and not the last. The classic cycle of abuse and apology had begun, and would continue for the next year, when Dorothy discovered she was pregnant.

Meanwhile, Leslie’s claims of wealth turned out to be lies. The couple lived first with his parents, and then in a cramped basement apartment in Omaha, Neb.—all Leslie could afford, because he was deeply in debt. And the beatings continued.

On July 14, 1913, the hottest day of the year in Omaha, Dorothy’s baby boy was born.

Leslie insisted he be named after him.

One day later, Leslie was ranting and raving at his wife. The doctor ordered him to back off and give his wife time to rest and recover. He also requested that a nurse remain in the house around the clock. In turn, the new father demanded both the nurse and Dorothy’s mother leave, threatening to shoot his wife if they didn’t.

But they held their ground and sent an emergency telegram to Dorothy’s father, who took the next train, hoping to mediate the crisis. Leslie admitted separation was a good idea. But immediately

after Levi Gardner departed, Leslie’s mood changed again. At one point, he threatened everyone in the house—mother, baby and grandmother—with a butcher knife. The

police were called. Tensions cooled, but soon flared up once more. Again, Gardner was summoned. He returned, but this time was unable to see Dorothy because Leslie had just gotten a court order blocking her family.

The situation was growing desperate.

Unbeknownst to Leslie, Dorothy called a lawyer, who told her to leave with the baby—immediately.

And so with the nurse watching out for her mentally unstable husband, Dorothy wrapped her little boy in a blanket and slipped quickly and quietly out of the house. She didn’t even stop to pack a bag. Running quickly down Woolworth Avenue in the heat of summer, she hailed a carriage, which took her out of the city and across the Nebraska/Iowa border to the city of Council Bluffs. There she met up with her parents and the four of them boarded a train for Chicago.

Dorothy filed for divorce. In December 1913, an Omaha court found Leslie King “guilty of extreme cruelty” and ordered him to pay $3,000 for back

alimony and $25 a month for child support. Furthermore, Dorothy, who was now living with her sister and brother-in-law in Oak Park, Ill., was awarded full custody of her little boy.

But King refused to pay a dime. When a court tried to seize his assets, they found he was broke.

His father, Charles King, agreed to pay the monthly child support for his grandson, a practice he would continue until the stock market crash of 1929 wiped out the family’s fortune.

The Gardners felt as though Dorothy’s divorce would bring shame to the family in Harvard—so they relocated to Grand Rapids, Mich., and invited their daughter and grandson to move in with them.

A Fateful Meeting at Church

In 1915, Gerald Ford Sr. was 24 years old, making a good living selling paint and varnish to the many furniture manufacturing plants in Grand Rapids. One evening, he decided to attend a social event for singles at the Grace Episcopal Church, where he met Dorothy. A year-long courtship followed, and they were married on Feb. 1, 1916.

Gerald Ford, Sr. was everything Leslie King was not. He was disciplined, courteous, respectful, steady and even-tempered. He was conservative, too, a faithful church attender. He meant what he said and said what he meant. He loved children, and immediately accepted his new stepson as his own.

“He was the father I grew up to believe was my father, the father I loved and learned from and respected. He was my dad,” the former president later recalled.

Ford’s parents waited until he was 13 to explain to him about the divorce and remarriage.

“It didn’t make a big impression on me at the time,” he would later say. “I guess I didn’t understand exactly what a stepfather was. Dad and I had the closest, most intimate relationship. We acted alike. We had the same interests. I thought we looked alike.”

Unlike many adopted children, Ford didn’t have much interest in meeting his biological father. “I had never met the man she said was my father,” he reflected. “I didn’t know where he lived, couldn’t have cared less about him. Because I was as happy a young man as you could find.

“I was so lucky that my mother divorced my [biological] father, who I hate to say was a bad person in many respects. She had a lot of guts to get out of that situation. When she moved to Grand Rapids and married my stepfather, that was just pure luck. We had a tremendous relationship, Dad and I.”

Growing Up in Grand Rapids

Gerald eventually gained three brothers, Tom (1918), Dick (1924) and Jim (1927). Ford’s father was intentional, and went to great effort to spend concentrated time with each of his sons, fishing and playing sports. “He believed sports taught you how to live,” the president wrote, “how to compete but always by the rules, how to be part of a team, how to win, how to lose and come back and try again.

“[My father] drilled into me the importance of honesty,” said Ford. “Whatever happened, you were honest. Dad and Mother had three rules: Tell the truth, work hard and come to dinner on time. Woe to any of us who violated those rules.”

The boys’ father modeled those standards outside the home while running his business, the Ford Paint and Varnish Company. When the economy took a nosedive and companies were closing all over the city, Gerald Sr. told his employees he was going to keep them employed, but cut their pay—and his. “We can pay you $5 a week to keep you in groceries, and that’s what I will pay myself,” he told them. “When times get better, we will make up the difference between the $5 and your regular pay, however long it takes.”

Ford’s 12th birthday opened a world he was eagerly awaiting: membership in the Boy Scouts. Now old enough to enroll, the outdoor enthusiast quickly embraced all things scouting with Troop 15 in Grand Rapids. He earned his Eagle badge, scouting’s highest honor, in 1927, ultimately gaining 27 merit badges. It was one of his first great accomplishments and one that would stick with him the rest of his life.

“One of the proudest moments of my life came in the court of honor when I was awarded the Eagle Scout badge,” he told a group of Boy Scouts, shortly after being sworn in as president. “I still have that badge. It is a treasured possession. It is a reminder of some of the basic, good things about our country and a reminder of some of the simple but vital values that can make life productive and very rewarding.”

Confronting the Past, Looking Ahead

When Leslie King appeared inside Bill’s Place, Gerald Ford was understandably rattled, but agreed to meet with him. The lunch was anticlimactic. His biological father didn’t have any good answers for his son’s questions. How could he have acted like he did? Why didn’t he ever pay his mother the support the court ordered? In the end, King asked if Gerald was interested in coming to live with his new family. He flatly declined. Why would he want to do that? He was enjoying his life in Grand Rapids with the only parents he ever knew. They quickly parted ways and would only see one another sporadically until King’s death in 1941 at age 56.

Arriving home that night, Jerry was anxious about how to tell his parents what happened. “Telling (my mom and dad) was one of the most difficult experiences of my life. They did understand. They consoled me, and showed in every way that they loved me.”

Meanwhile, thanks to strong mentors and to the generosity of a high school administrator who believed in him, Ford was able to attend the University of Michigan, where he was voted the most valuable player of their football team his senior year. In 1935, he went on to coach boxing and football at Yale, and eventually made his way into its law school, from which he graduated in 1941. With the outbreak of World War II in December, he received a commission in the United States Navy and spent the vast majority of his service on the USS Monterey aircraft carrier.

After the war, Ford was introduced to Elizabeth Bloomer Warren, a one-time fashion model and dance instructor. They began dating, and married two weeks before Ford was elected to the House of Representatives for their home district in Grand Rapids. For part of their honeymoon, the couple campaigned at a political rally at a University of Michigan football game.

Ford served with distinction in the House of Representatives for the next 25 years, before being tapped to serve as Richard Nixon’s vice president after Spiro Agnew was forced to resign for tax evasion in 1973. He ultimately assumed the presidency in August 1974, following Nixon’s resignation.

Healer

After being sworn in by Supreme Court Chief Justice Warren Burger as the nation’s 38th president, Gerald Ford stood before several hundred people inside the East Room of the White House and tens of millions more on national television. He knew Job One was to restore trust and decency to a republic deeply battered by the controversy surrounding the Watergate scandal.

“My fellow Americans,” he declared, “our long national nightmare is over … Our Constitution works; our great Republic is a government of laws and not of men. Here the people rule. But there is a higher Power, by whatever name we honor Him, who ordains not only righteousness but love, not only justice but mercy.” A month later he pardoned Nixon. He did so not because he thought Nixon was innocent, but to spare the country the pain and drama of a long drawn-out trial. It was a selfless act, really, because it was an unpopular decision that all but insured he wouldn’t be elected in 1976.

At his core, until his death on Dec. 26, 2006, at the age of 93, Gerald Ford was an optimist, who looked for the best in everyone and everything, a trait his father modeled for him as a young boy. “Everybody has more good things about them than bad things,” he would say. “If you accentuate the good things in dealing with a person, you can like him even though he or she has some bad qualities. If you have that attitude, you never hate anybody.”

When he died, Wall Street Journal columnist and former speechwriter Peggy Noonan acknowledged those very same traits. “He didn’t indulge his angers and appetites,” she wrote the day of his death. “He seems to have thought, in the end, that such indulgence was for sissies—it wasn’t manly. He was sober-minded, solid, respecting and deserving of respect. And at that terrible time, after Watergate, he picked up the pieces and then threw himself on the grenade.”

How fitting that a boy whose first weeks of life were framed by struggle, strife and hurt would one day rise to a position where he would be called on to help lead his nation in a time of constitutional crisis. It was almost as if he had been groomed for the moment from the very beginning, which of course, he had.

“We were lucky to have him,” Noonan concluded. “We were really lucky to have him.”

For More Information:

Adapted from Chosen for Greatness:

How Adoption Changes the World, by Paul Batura.

Copyright ©2016. Published by Regnery. All rights reserved.

Used by special permission of Regnery. Washington, D.C.

Originally published in the November 2016 issue of Citizen magazine.