Mayhem, strikes, tragedies, wars, upheavals, terrorism, and calamities of all sorts — manmade and natural — make or break men and women who would emerge as important political leaders.

There are numerous examples. During the now-forgotten Boston Police Strike of 1919, a failed attempt by that city’s mayor at reconciliation with officers resulted in lawlessness and a profound sense of unease. The Massachusetts State Guard had to be called in. It became a national story overnight. Civil unrest led to nine deaths.

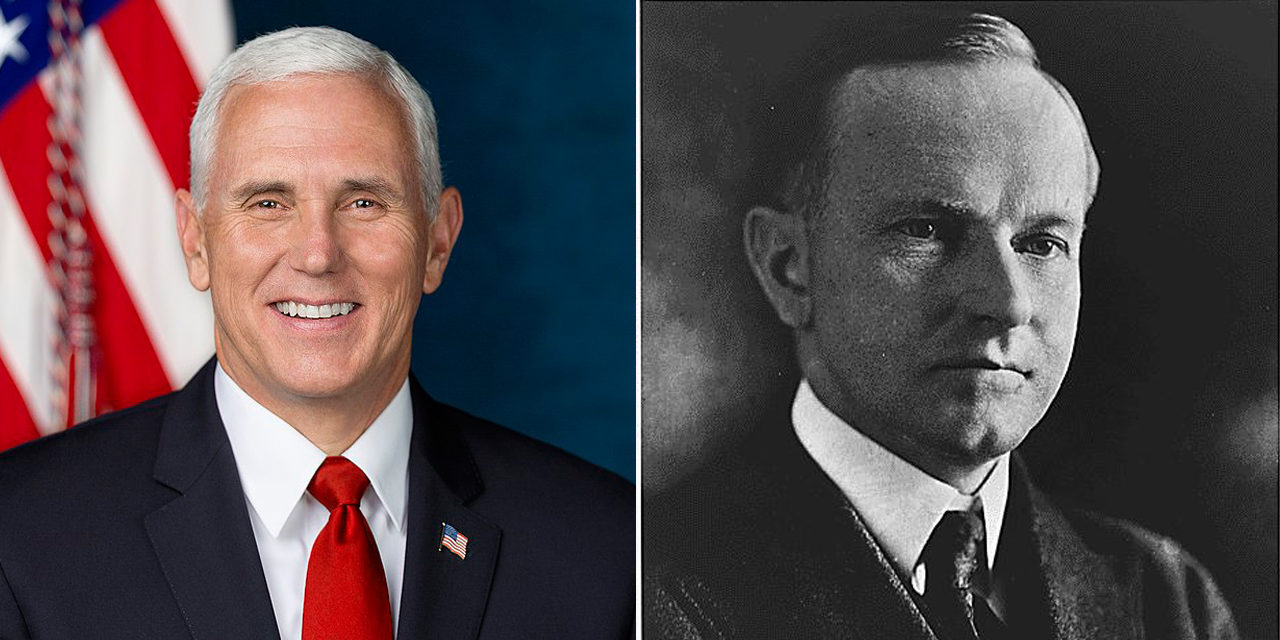

The governor of the state, little-known Calvin Coolidge, who was by nature prudent and calm as a spring day, famously admonished the police that they had no right to strike against the public’s safety, ever. Law and order amid chaos and disorder became the Coolidge calling card, but something even more important: personal attributes that came to define Coolidge were incarnated in that tumultuous New England moment. It was the burnishing of the man known as Silent Cal.

Coolidge’s steadfastness and stoutheartedness became an overnight sensation, and in 1920, plucked from near-obscurity, Coolidge became Warren Harding’s running mate on the successful GOP presidential ticket. As fate would have it, Harding died before the end of his term, and Coolidge became the President, sworn in by his justice-of-the-peace father while visiting his hometown, a small village in Vermont.

It wasn’t that Coolidge stormed into the middle of Boston mayhem; it was that his preternatural coolness, accompanied by welcome prudence and wisdom, showed the American people that leadership can be defined by the three attributes Coolidge would later highlight in his own reelection campaign of 1924: that he was ”safe, sane, and steady.”

The Coolidge paradigm is not unlike what our nation has witnessed in Vice President Mike Pence the last few weeks as the presidentially appointed Coronavirus Task Force leader. With self-assuredness and calm, he comes to the daily White House press room briefing podium well-informed and prepared. He’s comfortable deferring to the bevy of health and medical experts around him, and never feels rushed or hurried. There is no braggadocio about him, and his combination of clarity and good counsel has a way of defining the briefings as clear-eyed and affirming.

In multiple ways across the last two weeks, there were ample opportunities for him to have gotten flustered or beaten-down; instead, his candor and goodwill has the effect of evoking national unity, and the Vice President regularly finds ways to concretize areas of agreement instead of flagging bitterness or partisanship.

Even normally left of center journalists who cover the White House have had good things to say about the Vice President’s leadership during the crisis. The New York Times, for instance, said “Mr. Pence … gets good marks for how he [has] handled the White House response …”

He is certainly not above pointing out or engaging areas of disagreement; rather it is that he doesn’t dwell on those areas or become angry or mean-spirited or disconsolate. He has the gift of distinguishing mole hills from mountains, which in this era of the American public square is a refreshing oasis.

This has been a burnishing moment for Vice President Pence, and as with an athlete of great skill and understated ability finding his métier, fair-minded people of both political parties, and everyone from progressives to libertarians, have witnessed in him the kind of equanimity and objectivity that comprise the virtues of not only a model public servant but also great leadership in a time of crisis and a war against a lethal, invisible pathogen.

One gets the sense that Pence’s confidence and equipoise under pressure is rooted in the grace and goodwill of his faith. If there is ever a time we have needed the second most powerful man in our country to telegraph that assuredness and calm, it is now. We’ve watched, it seems to me, the burnishing of Mike Pence, and it is the pathway of talented leadership defined by humility and an understated elan.

It is a sensibility that echoes Coolidge who, like Pence, believed religion played a central role in American governance, and that personal faith on the part of leaders and citizens directly impacted the tone and tempo in the public square. Coolidge said: “Our government rests upon religion. It is from that source that we derive our reverence for truth and justice, for quality and liberality, and for the rights of mankind. Unless people believe in these principles they cannot believe in our government.”