___________________

“If what Christians say about Good Friday is true, then it is, quite simply, the truth about everything. Good Friday is the drama of the Love by which our every day is sustained.”

Richard John Neuhaus, Death on a Friday Afternoon

___________________

As we celebrate Good Friday, which was anything but for our Savior and His disciples, The Daily Citizen and Focus on the Family would like to share with you a few classic paintings of the crucifixion drama and some reflections upon them.

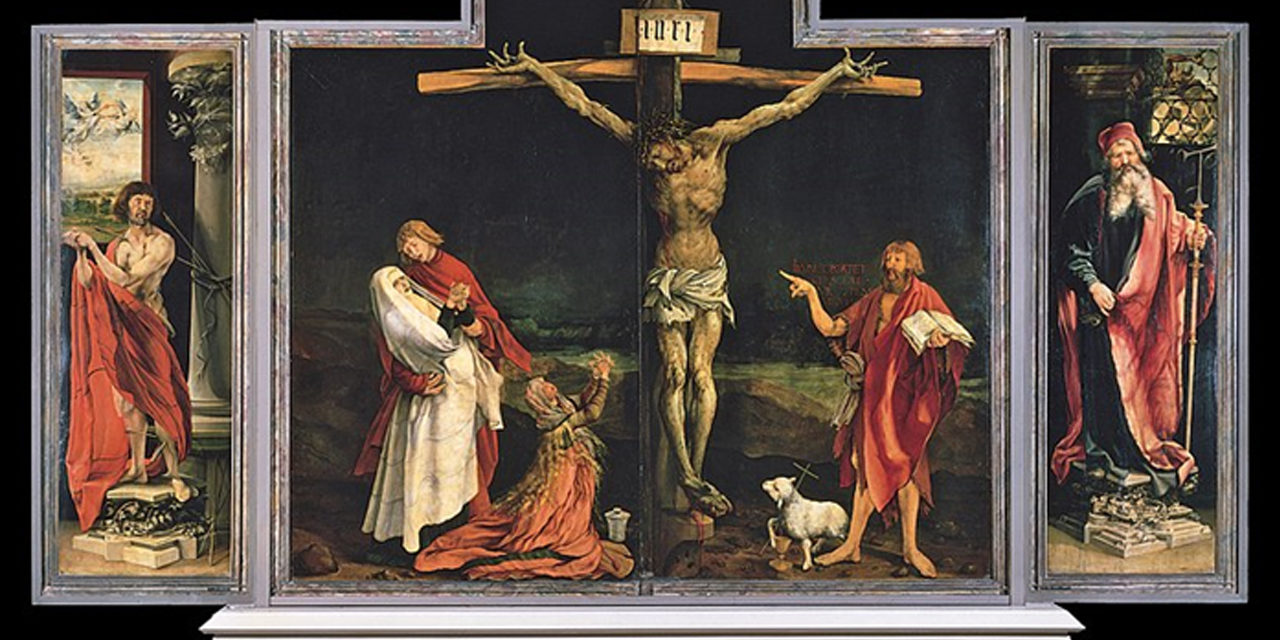

The first is a very curious and more contemporary interpretation of what happened on Good Friday, reminding us that the cross of Christ is timeless.

This is Marc Chagall’s White Crucifixion, done in 1938. Chagall was a French painter of orthodox Jewish origins. He wants to remind us of our Savior’s Jewish faith, as he replaces Jesus’ loin cloth with a prayer shawl as well as other Jewish imagery. I take all the other activity as a reminder of why Christ came: to defeat sin, hell and death. He redeemed and is redeeming amid great darkness. This is a wonderful recollection of the power of the Cross from a man of deep Jewish roots.

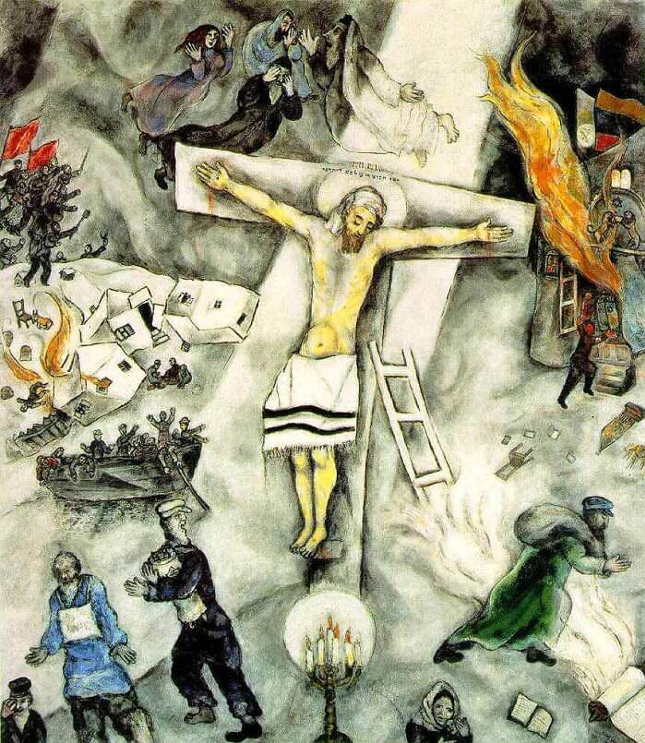

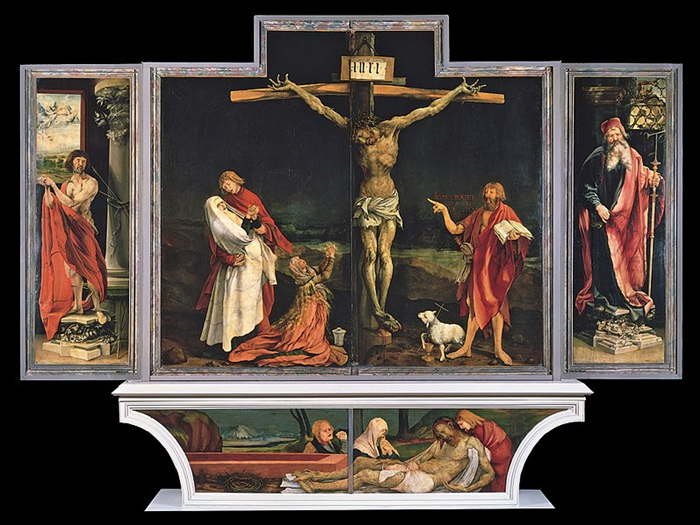

This second painting is arguably the most dramatic painting of our Lord’s passion on the cross as it is certainly one of the most honest and realistic. It is the Isenheim Altarpiece, created in 1515 by Matthias Grünewald, a German Renaissance painter.

It is difficult to come up with another major painting of the crucifixion that communicates the horrendous abuse our Savior suffered as does Grünewald’s. Our Lord’s twisted, mangled, brutalized body. His fingers ghoulishly contorted in pain, but also as if they are raised in total submission to His Father’s will and surrender to the desperate need of humanity.

Grünewald presented Christ this way for a very specific and practical reason. It has to do with who he painted this altarpiece for. It was created to sit in the chapel at the Monastery of St. Anthony. This was a place where those suffering from ergotism, an epidemic poisoning that ravaged its victims with terribly painful skin ailments, came to live for comfort and healing. The disease went by the more popular name St. Anthony’s Fire due to the work of the monks here who were quite successful in relieving it victims from suffering. Grünewald wanted to present an image of Jesus as the Savior who could well identify with their suffering as His was even more intense. Grünewald’s Jesus bore the same kinds of sores that those suffering from the Fire did. He can relate to our suffering.

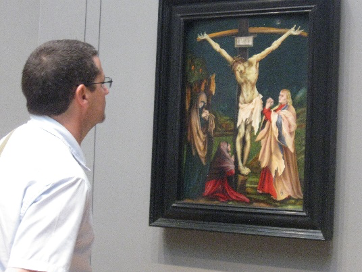

A very similar representation is Grünewald’s Small Crucifixion which hangs in the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC. I’ve had the pleasure of viewing it in person.

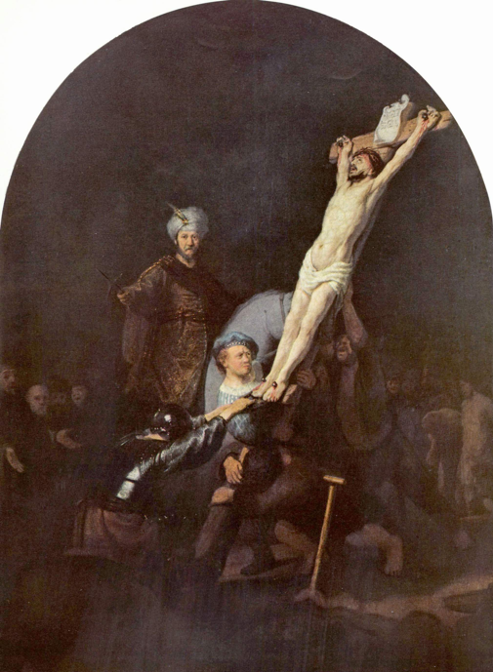

The final portrayal is tremendously dramatic, not so much in how the Savior is portrayed, but for who else appears in the painting. This is Rembrandt’s The Raising of the Cross painted in 1633. There are two curious people presented in this work and what they represent is interestingly just as important as the image of Christ himself because they tell us who put Him there and why.

They are the only other two characters bathed in light. One is the person in the blue beret struggling to raise the cross of Christ. That is Rembrandt himself. Is he telling us he was there historically, taking part in the crucifixion? In a way, yes. He is telling us that it was his sins, Rembrandt’s alone, that put Christ on the cross. He is the guilty one. Of course, that is true of all of us, for we all have sinned and fallen short of God’s holiness. We each need redemption and forgiveness and are eternally lost without it. Thus we are the ones that made Christ’s death on the cross necessary. He is there because of you and because of me. That is precisely what Rembrandt is telling us.

Behind him, there is another man. This is Rembrandt as well. He is looking straight at us, the viewers. Dead on. We cannot ignore him. He is mounted on a horse and holding a small cross in his right hand. He is asking each one of us if we understand our own place in the terrible death of Christ on the cross. Just as Rembrandt is responsible for Christ’s execution, so are we. Just as true, we all have the command to tell the world this story. That is the message of this unique and transfixing painting.

__________________

“He forgave us not by ignoring our trespasses but by assuming our trespasses… God became what by right he was not, so that we might become what by right we are not.”

-Richard John Neuhaus, Death on a Friday Afternoon

__________________

This is precisely what these three wonderful paintings are about. God who is holy became sin so that we who are sinful might become holy. Let us end with one additional, but different, special reflection. This is Peter Paul Rubens’ The Entombment (1612) which immediately seizes the viewer.

In stark contrast to the most famous Pieta in Rome, Rubens’ representation is dramatically human. It grabs the heart, not for its beauty which is certainly there, but for the realism of our Savior’s lifeless, pierced and bleeding body as well as the agony of a real mother holding her dead son. It grabs you. Rubens has us look upon Mary not so much as a heroic biblical figure, but as a mother, like any other. Look at her eyes.

She has not just been crying. They are stained red, bloodshot, worn out with the agony that she has been suffering. She is looking upward. What is that about? Just as her son asked His Father why He had been forsaken, Mary is asking the same thing. It was not supposed to end like this.

Perhaps that is the Apostle John supporting the Savior’s body, as he was asked by Christ while on the cross to care for his mother. Take note of what Christ’s body is laying upon. A stone block, symbolic of the cornerstone, which is Christ, who the builders rejected. Note the wheat straw, symbolizing both life and sustenance which His death brings us. But it also reminds us of the manger’s hay that supported him at his birth.

It is a remarkable, highly dramatic work that shows us that Christ’s life and death happened in the real-life drama of an actual family, visited by all the joys and pains humans endure.

This is our Savior’s story. Let us take it in on this Good Friday … and beyond.