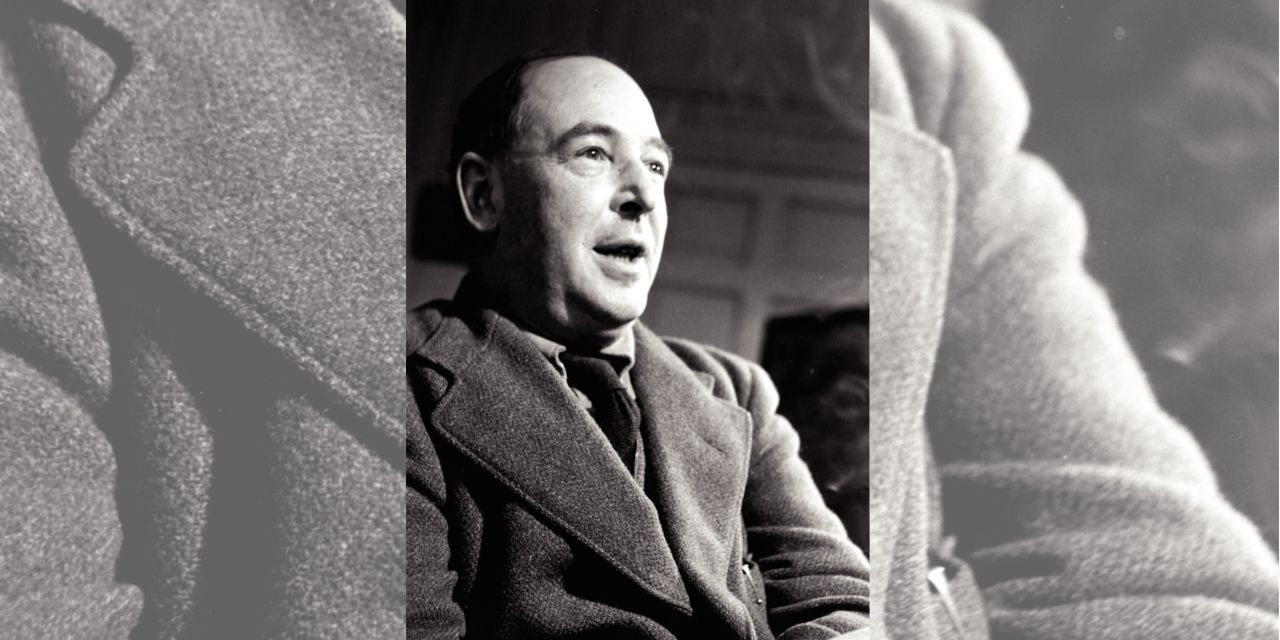

This coming Thanksgiving Eve, November 22nd, will mark the 60th anniversary of the deaths of three household names: President John F. Kennedy, Aldous Huxley, and Clive Staples Lewis – known forevermore as “C.S. Lewis.”

That these three very different but very public men all died on the same day has long been a point of intrigue. But of the three, at least for Christians, Lewis likely remains the most quoted and long lasting. His more than 30 books are considered timeless and classic and continue to appeal to new generations.

But Lewis’ final work wasn’t a book but an essay, a project that consumed some of his final days the last week of his life. It would be published in the December 11th, 1963, edition of the Saturday Evening Post. He titled it, “We Have No Right to Happiness” – a remarkably prescient piece that offers yet one more example of why so many have loved the English writer for so long.

If the subject of happiness was considered a popular topic back in 1963, it’s a barnburner theme in 2023. Hundreds of books on the subject are published every year, joining the tens of thousands of similar titles already in the library. Since the beginning of time, mankind has been searching for it – and maybe never more than now.

As a reminder that the more times change, the more things remain the same, Lewis opened his essay describing an extramarital affair motivated by a dissatisfied couple searching for bliss in an illicit relationship.

“But what could I do?” he quotes one of the guilty parties. “A man has a right to happiness. I had to take my one chance when it came.”

Only Lewis wasn’t buying it.

“A right to happiness doesn’t, for me, make much more sense than a right to be six feet tall, or have a millionaire for your father, or to get good weather whenever you want to have a picnic,” he reflected.

Lewis goes on to acknowledge a universal desire for wellbeing, even noting America’s enshrinement of the “pursuit of happiness” in our Declaration of Independence. But like he had a knack for doing, the famed author cuts through the fog and zeroes in on what is really behind the motivation in this instance: sexual happiness.

Here’s how he describes the thought process of those who rationalize adultery or promiscuity in a quest for personal satisfaction:

Sex was to be treated as no other impulse in our nature has ever been treated by civilized people. All the others, we admit, have to be bridled. Absolute obedience to your instinct for self-preservation is what we call cowardice; to your acquisitive impulse, avarice. Even sleep must be resisted if you’re a sentry. But every unkindness and breach of faith seems to be condoned provided that the object aimed at is “four bare legs in a bed.”

Despite writing this over sixty years ago, Lewis has identified the root of the ongoing sexual revolution that roils culture today. You might say it’s always been, but there’s no doubt it’s progressiveness is making a bad situation much worse.

Lewis goes on to warn that sexual sin harms everyone but especially women “who are more naturally monogamous than men.” He also rightly cautions that sexual sin once contained between only two people inevitably spreads to harm others – and that its recklessness eventually seeps into every other aspect of our lives.

Many read Lewis’ classic works to be entertained, charmed, and ultimately enriched. This last work should be read to be warned and reminded that true sexual happiness will only be found within the confines of marriage.

Image from The Wade Center.