Don’t Fall for Social Media Rage-Bait: Here’s What To Look Out For

JUMP TO…

Social media warriors, beware — that stranger you schooled in the comment section might be goading you into a fight.

It’s called rage-baiting, and its online content creators’ latest strategy to turn your clicks, views and comments into cold, hard cash.

In the middle of a contentious election season, Christians now more than ever must recognize and avoid these manipulative invitations to indulge in social media mudslinging.

Here’s what you need to know.

Rage-baiting only makes sense in the context of the online economy, which runs on advertising.

Content creators, from legacy media outlets to fledgling social media influencers, make money by allowing companies to advertise with them. But businesses won’t advertise just anywhere — they need assurances that people will see the ads they pay to place.

That’s where you come in.

Social media websites keep detailed records of users’ engagement — the content they watch, how long they watch it and whether they like, share or comment on it. Creators can show these metrics to businesses to demonstrate how many people will view and click on their advertisements.

If content creators need advertisements to make money, and businesses are more likely to advertise with creators that get engagement — views, clicks, follows, shares, comments, likes, ad nauseum, then that means content creators have incentive to get you to engage as much as possible.

Enter rage-baiting.

If you’ve spent any time on the internet, you’ve probably encountered clickbait — sensational and frequently misleading content meant to entice viewers to click on a hyperlink.

Rage-baiting is clickbait’s more manipulative cousin. Instead of creating content to drive viewers to a link, rage-baiters drive viewers to watch, comment and share by making content designed to enrage people.

Rage-bait takes many forms — a contrarian comment under a political photo, a staged TikTok of someone yelling at a woman with a baby, a video of someone making a wasteful or gross meal, even videos of influencers putting on too much makeup — but all have two things in common: they are intended to inspire anger and designed to deceive.

Let’s look at a couple of examples.

- A post from Independent Women’s Forum (IWF) on men competing in women’s boxing at the Olympics? Not rage-bait. Reporting or commenting on a genuinely outrageous event is not the same as fabricating something for users to be angry about.

- A TikTok video, unearthed by The Tab, showing an elderly woman yell at a mother and her baby on a plane? Rage-bait. The video is clearly staged and acted to cause outrage. Look closely — there’s not even a baby in the “mother’s” blanket!

- A post from the Daily Citizen asking readers to comment on biblical masculinity and femininity? Not rage-bait. Posts that clearly solicit engagement aren’t manipulating people into a reaction — angry or otherwise.

Rage-bait works because advertisers don’t care whether engagement is positive or negative. Angry comments, incredulous shares and views from disbelieving critics inflate rage-baiter’s social media metrics just the same as positive engagement.

As Medium contributor Peter Silva reflects, “We’re the ones helping [rage-bait] get the views, comments, and virality we are shocked to see it get.”

So, why rage-baiting? Why not “amusement-baiting,” or “sad-baiting” or “confusion-baiting”?

More than a decade of research suggests anger makes people more likely to engage with online content than any other emotion.

In 2009, researchers from the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania conducted a series of experiments involving 147 people and 7,000 New York Times articles. Investigators discovered people were more likely to email around stories that inspired high-intensity emotions like anger, anxiety and awe.

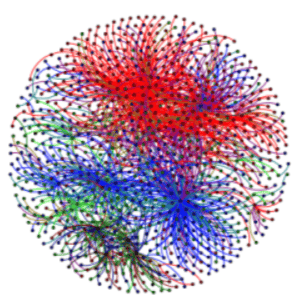

A subsequent study of joy, sadness, disgust and anger on Weibo, China’s version of Twitter, confirmed the Wharton School’s results. Of the 70 million comments analyzed, researchers from Beihang University determined those conveying sadness and disgust — low-intensity emotions — didn’t spread as far as the high-intensity emotions of joy and fear.

Further, the study determined anger spread the farthest by far:

This graphic illustrates the spread of messages containing emotions, with anger (red) overtaking joy (green), sadness (blue) and disgust (black).

The importance of social media literacy grows every day as global discourse continues to migrate online.

But recognizing and resisting rage-bait is particularly important during times of political turmoil.

A 2020 analysis from Cambridge discovered rage could be used as a potent political weapon. The study of 2.7 million tweets and Facebook posts from US media outlets and Congresspeople concluded:

Even more shocking, a concurrent analysis of the Times’ Twitter and Facebook posts found:

Cambridge’s findings only confirm the past decade’s research. The Chinese study of Weibo from 2010 found angry posts were most often inspired by “international conflict and domestic problems.”

Political anger is content creator’s proverbial white whale. All they have to do is sit back and watch the money roll in. Meantime, strangers eviscerate each other in the comment section and thoughtful discourse becomes a pipe dream.

It’s incumbent upon Christians, who are called to a higher standard of conduct, to hop off the crazy rage train. Here’s what you can do.

Your best defense against rage-bait is to refrain from engaging. Don’t comment. Don’t click. Don’t watch. You might be tempted to comment something like, “Don’t give this any more attention! It’s just encouraging them.” Resist the urge.

If you feel you must engage, give yourself five seconds to confirm that the post isn’t rage-bait. Try out some of these strategies:

- Check the comments: If other users suspect the video is fake, chances are some will post about it.

- Look for all or nothing language: Posts making broad claims about large groups of people (i.e. all Christians are extremists) are likely rage-bait.

- Look for invitations to conflict: Some rage-baiters preface posts with phrases like “hot take” or “unpopular opinion” to increase the likelihood that people will react.

- Check the details: Misspellings, lack of punctuation, overuse of emojis, poor editing and over the top acting are all clues that a piece of content could be rage-bait.

- Look at who’s posting: Many rage-baiters don’t interact with social media the same way regular people do. If you answer “no” to any of these questions, this user might be a rage-baiter.

- Do you know this content creator?

- Do they have friends on Facebook?

- Do they divulge any information about themselves, like where they work or where they went to school?

- Do they post any pictures of themselves or their friends?

- Do they routinely post crazy opinions?

Social media can be a sketchy place. Take these steps to avoid manipulation and rage-bait, engage with content you actually want to support, and behave as a representative of Christianity in a strange land.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Emily Washburn is a staff reporter for the Daily Citizen at Focus on the Family and regularly writes stories about politics and noteworthy people. She previously served as a staff reporter for Forbes Magazine, editorial assistant, and contributor for Discourse Magazine and Editor-in-Chief of the newspaper at Westmont College, where she studied communications and political science. Emily has never visited a beach she hasn’t swam at, and is happiest reading a book somewhere tropical.

Related Posts

‘Land of Lincoln’ Looks to Bully Homeschool Families

April 3, 2025

Matt Walsh and a Call to Wake Up a Weary World

April 2, 2025

Stop Lying to Women

April 2, 2025