Commencement addresses have become, on far too many American college campuses, predictably star-studded events with equally predictable patterns.

Steven Spielberg, James Franco, Oprah Winfrey and other Hollywood grandees sweep onto elite college and university stages nationwide, offer up 20- to 30-minute addresses replete with references to “hot” political or cultural trends or topics, and exit stage left to sometimes-deafening applause.

In an age of celebrity, ask the typical graduate what he or she remembers from his or her commencement address a mere two or three years later, and it’s common to receive blank stares. Speech after speech, year in and year out, too many speakers have left students and parents alike a little hollow from the sometimes- superficial nature of the enterprise.

This is both a shame and a wasted opportunity. Commencement addresses should nourish young minds, hearts and souls with something of the beautiful, the just and the true.

In preparation for this article, I went back in collegiate and academic history to read some memorable commencement addresses. I was pleasantly surprised, for instance, that some U.S. presidents had vividly recalled not only the commencement remarks of their youth but also how the speakers indelibly impacted their later lives and key decisions.

Remembered Words

For instance, President George H.W. Bush, 50 years after his graduation from Andover, proclaimed the direct influence the commencement speaker made on his career path. What a testament to the potential power for good of one speech, one set of ideas, and one well-wrought oration in the groves of American higher learning.

It’s a rare thing now—like finding a diamond in the rough—to personally witness or read such a commencement speech. Yet when it happens, it’s like witnessing Haley’s Comet: The flash across the sky might be uncommon, but its luminosity makes the richness and brilliance of the phenomenon all the more valuable.

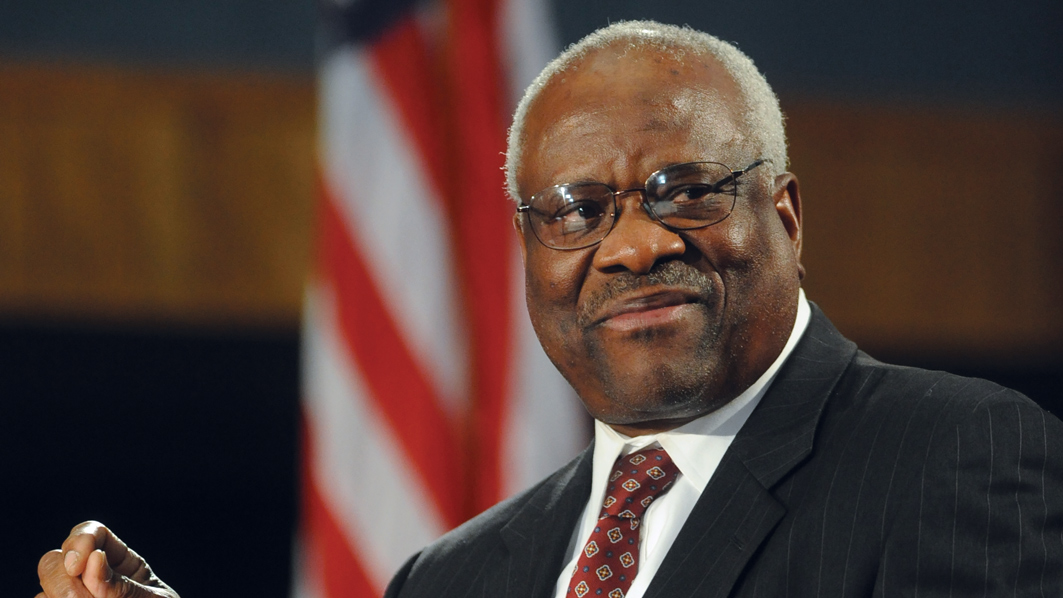

Such was the case with Supreme Court Associate Justice Clarence Thomas’ clear, accessible, and concise commencement address at Hillsdale College this past May. Titled “Freedom and Obligation,” it is a tour de force. It was the 164 th such commencement at that small liberal arts college in Michigan, but it will be remembered as one of the finest. It is such an affecting speech, and delivered with such sincerity, warmth and brio, that it could well become part of any curriculum on what it means to be a great citizen.

With surgical precision, Thomas asserts that the other side of freedom is responsibility –that there is a vital relationship between duty and sacrifice on one hand and a thriving constitutional republic on the other. He says liberty comes with deep and abiding obligations, the most important of which is to live with integrity expressed in often small and unrecognized ways.

He says individuals committed to fulfilling their responsibilities are the necessary glue that keeps a free society thriving.

Great citizenship, Thomas avers, is rarely flashy, but it is ultimately responsible for defending those first and unchanging principles that undergird our greatest national institutions.

There is a tone and tempo to Thomas’ remarks that are sobering and quietly authoritative, and he doesn’t mind telegraphing a bit of a lament about the impact of our coarsened culture.

“Things that were considered firm have long since lost their vitality,” said Thomas, “and much that seemed inconceivable is now firmly and universally established. Hallmarks of my youth, such as patriotism and religion, seem more like outliers, if not afterthoughts.”

Substance and Style

Throughout the speech, with characteristic insight and subtlety, Thomas irreducibly and seamlessly weaves these informed observations into his own personal experiences in a manner that is both biographical and refreshingly clear-eyed. He studiously avoids the typical Olympian commencement speaker pose and instead chooses a more affable and humble approach defined by its crystalline articulation of what really matters in a society committed to self-government.

Although he does not mention or reference his memoir, My Grandfather’s Son, during the course of his speech—one of the most self-revelatory and transparent books ever written by a Supreme Court justice in the history of that august institution—Thomas does reference the most impactful person in his life.

He recalls that even in the highly segregated South of his youth, his grandfather had an unwavering view of biblical human relationships: “Being wronged by others did not justify reciprocal conduct. Right was right, and two wrongs did not make a right.” Simple, elegant, bold.

“I resist what seems to be the formulaic or standard fare at commencement exercises—a broad complaint about societal injustice and an exhortation to the young graduates to go out and solve the problem and change the world,” he said. “Having been a young graduate myself, I think it is hard enough to solve your own problems, which can sometimes seem to defy solution.”

What makes this appeal so heart-rending is its recognition that we are all fallen and sinful people, and that we all have inherent limits as fallible men and women of what we can do to actually impact the world around us.

Instead of summoning the graduates to a seek a utopian vision that is ultimately unattainable, Thomas encourages his listeners to be both self-reflective and willing to be morally accountable for their own actions in their family circles, with their friends and neighbors, and in the communities in which they live and work. Such actions, he said, will have the net effect of widening the scope of freedom in the place where God has put us.

“Today, we rarely hear of our personal responsibilities in discussions of broad notions such as freedom or liberty,” he said. “It is as though freedom and liberty exist wholly independent of anything we do, as if they are predestined … in addressing your own obligations and responsibilities in the right way, you actually do an important part on behalf of liberty and free government.”

With a dash of style, Thomas says that instead of the students trying to dedicate their lives to the redemption of the world, they should instead begin with their own lives and the manner in which they treat those closest to them.

He says this kind of personal moral responsibility and sacrifice is what the founders of America believed in so deeply and unwaveringly in creating the freest country in the history of the world. This mutuality between personal character and the community around us is the central narrative of Thomas’ great speech.

The Benefits of Liberty

“There is always a relationship between responsibilities and benefits,” Thomas said. “If you continue to run up charges on your credit card, at some point you reach your credit limit. If you continue to make withdrawals from your savings account, you eventually deplete your funds. Likewise, if we continue to consume the benefits of a free society without replenishing or nourishing that society, we will eventually deplete that as well. If we are content to let others do the work of replenishing and defending liberty while we consume the benefits, we will someday run out of other people’s willingness to sacrifice.”

Using that simple, graspable illustration, Thomas eloquently draws a direct parallel between liberty and obligation, between freedom and duty.

Near the close of the speech, and with a touch of moral ardor, Thomas personalizes this principle by sharing with the Hillsdale audience how he had gone to his grandfather to convey his deep frustration over the bitter criticism and calumny that had been hurled at him during one of the deepest moments of his life in the early 1980s.

He conveyed that his grandfather’s advice was both tender and inspired: “Son, you have to stand up for what you believe in.” For Thomas, this was a moment of clarion duty for all that he was raised to believe. It telegraphed the need for empathy, fortitude and the foundations of faith and grace amid the most troubling moment of his experience.

“As you go through life, try to be a person whose actions teach others how to be better people and better citizens,” he said. “Reach out to the shy person who is not so popular. Stand up for others when they’re being treated unfairly. Take the time to listen to the friend who’s having a difficult time. Do not hide your faith and your beliefs under a bushel basket, especially in this world that seems to have gone mad with political correctness.”

What did all this add up to for the newly minted graduates and their families? That these obligations, fulfilled with endless character, “become the unplanned syllabus for learning citizenship … a beacon of light for others to follow.”

Thomas’ own tenure has been a testament of this great challenge—defined by the eminence of a statesman, unflappable poise and a tireless and relentless striving for justice.

On the day I reread parts of Thomas’ great speech, a friend sent me an essay quoting the great Russian novelist Leo Tolstoy: “Everyone thinks of changing the world, but no one thinks of changing himself.” Just so.

The refreshing clarity and brilliance of Justice Clarence Thomas’ Hillsdale commencement address is a supple and seasoned reminder that freedom is not free; that by serving God and others first and ourselves last, there is a tangible benefit to our community and our country; and that by better understanding the invaluable relationship between virtue and liberty, we come to see that in order for freedom to flourish, we have promises to keep that demand unwavering allegiance and moral excellence.

Justice Thomas, a great-souled public servant and devoted keeper of the constitutional flame whose life on the bench has been defined by its grace and intelligence, has shown us that taking personal responsibility for our own lives and actions while acting with holy courage is the healthy and indispensable foundation of great citizenship.

Originally published in the December 2016 issue of Citizen magazine.