I could start off by saying there’s some special secret magical experience to having a brother with Down syndrome. It’d be easy to spin a heart wrenching tale that makes my brother Greg’s story a tearful revelation, like the end of an episode of Touched By An Angel. But I worry that doing so might run the risk of reducing him to a teaching aid. And while using a sibling for purposes other than designed (scapegoat, punching bag, fall guy in a pyramid scheme) is well‐established, it wouldn’t be accurate. I don’t want to run the risk of making my brother, or anyone for that matter, a character in a fable. His story is more complicated than that.

Which is to say, he’s a lot more normal than you might expect. So was the experience of growing up with him. But Greg’s “normal,” like anyone’s “normal,” is complicated and weird. I’m reminded of the line from Ferris Bueller’s Day Off: “I used to think my family was the only one that had weirdness in it. That used to worry me.” Like Ferris, the years have taught me that every family, and every person, is weird. And weirdness abhors a fable. The closer you look, the less Greg is like one of Aesop’s foxes or dogs or crows, and the more he’s like a character in a novel. Say, Stephen Daedalus or Holden Caulfield…just far less annoying.

So, I’m better served talking about my experiences with Greg. Which are rambling and complicated. Like any relationship.

My brother, my self

Greg and I are pretty different. He’s an extravert and a drama kid. I’m an introvert and a writer. Greg’s personality is gregarious and sometimes extravagant. I am private, and would rather staple gun my toes together than be the center of attention. What all this adds up to is that we’re an odd couple at parties. Greg wants to meet people. If I’m with him, he’ll want to introduce me. I’ll want to find a corner where that’s less likely to happen. Greg, gregarious as ever, will try to stop that from happening.

That gregariousness runs deep. At the age of five, Greg broke off from a scripted dance routine in his preschool recital and spent a full minute freestyling downstage, to riotous applause, before his partner could pull him back into formation. Mind you, a five‐year‐old’s freestyling looks like wild, Beto O’Rourke arm gesticulations. Greg, unlike O’Rourke, made it work. Then he broke formation a second time and made it work, again, to louder applause.

I love that story, but realize even it strays somewhat close to fable territory. What’s the day‐to‐day of our relationship look like? Trying to relate to each other, looking for things we can agree on, remembered inside jokes, occasional communication breakdowns, fights that we’ve made up over, shared life experiences, being glad to see each other despite all this, being grateful for the way baseball season provides actual conversational material. Again, it defies easy categorization.

I’m proud to say I got him to crawl. We had tried for weeks. It was tough for Greg, children with Down syndrome have lower muscle tone. Their developmental milestones tend to come later than with normal kids. Also, he shares in the family stubbornness. One afternoon in 1992, I found myself seated on a blanket in my bedroom, attempting to get Greg to crawl towards me with the aid of a few saltines, his favorite solid‐food snack. Mom was in there with us, and after several minutes of trying, left to answer the phone.

I was getting bored. The thing they don’t tell you about baby siblings is that the cute factor’s effective in small doses, but wears off after a few minutes. So, I got my micro machine aircraft carrier, opened the front storage hatch, and dumped several decades of military aviation onto the blanket: Phantoms, Warthogs, Tomcats, and a hunting‐vest orange spy plane. Greg’s eyes lit up. He laser‐focused on the miniature X‐1, and somewhere Gary Powers’ ears must have burned, because Greg immediately flopped forward onto his hands and crawled towards the toy with the enthusiasm of a Soviet antiaircraft missile.

“MOM! MOM!!!” She came running, and was equally as thrilled as I was. Is there a lesson here? Thank the Lord, no. There’s an experience: one that makes me smile on a rainy afternoon in the middle of a half‐successful job hunt twenty‐odd years later. While there’s no easily‐taken lesson, there is a memory of the way family members’ lives intertwine. That intertwining is more complicated and beautiful than a moral summation. Edward Hopper once said that if he could paraphrase what was happening in his paintings, there’d be no reason to paint them. Growing up with Greg, as with anyone, was the same.

Point/Counterpoint

This is not to say that raising a child with Down syndrome is easy, or that I mean to be flippant about the feelings of expectant parents. The challenges of raising a child with this condition are unique. However, I’m writing this from the perspective of a sibling, and not a parent. From that different perspective, the difficulties are counterbalanced by having a life made fuller by another family member. From the sibling’s point of view, the kid is not a cataclysm or a cause for concern. They’re another family member, with all that entails. Some kids will find the new baby fun and exciting. Or, if you’ve got an only child who doesn’t want a sibling, they’ll find a new baby annoying. Or, if you have a kid who’s dying for a little brother or sister, the new kid will be a boon. While the diagnosis may be scary for the parents, what your current or future kids will experience from a sibling with Down syndrome isn’t consternation or fear. It’s the complicated, haphazard fullness of human experience, with all that entails. That’s something that defies easy categorization, whether in a fable, an op‐ed, or a policy.

It’s impossible for me not to compare a child’s openness to the sterile myopia of many politicians and academics. For instance, there’s hatemonger Richard Dawkins, telling a woman who had a baby with Down syndrome to murder her newborn child and “start over.” There’s any number of politicians who mournfully speak of differently abled kids as “burdens,” then coincidentally receive thousands from Planned Parenthood, who account for many of the 67‐85% of babies with a prenatal diagnosis of Down syndrome murdered in the womb. There’s the anonymous high‐achieving father who actually said, “if he can’t grow up to have a shot at being President, we don’t want him.” I’d be well within bounds to call those people’s myopia, monstrous. But that would reduce them to characters in a fable, too. Thinking of the openness Greg inspires, I realize hating them is too simplistic a response to their ignorance. Instead, I feel a subtler and more difficult emotion: pity. How can anyone see the complexity, interconnectedness, and haphazard beauty of any life as a “burden?”

But I could be missing the bigger picture. I don’t care for fables, but maybe the Primum Mobile does. Maybe there is fable‐like purpose behind Greg and I having been born to the same parents. But that’s not something I’ll know, in any full sense, while still alive. In the meantime, all any of us can do is accept the frustrating, beautiful, happenstance way normal is complicated, and complicated is normal.

Navigating the tension between those two is, I’d argue, a decent characterization of the human experience. It’s also a decent characterization of faith.

Contact Geoff Hoppe

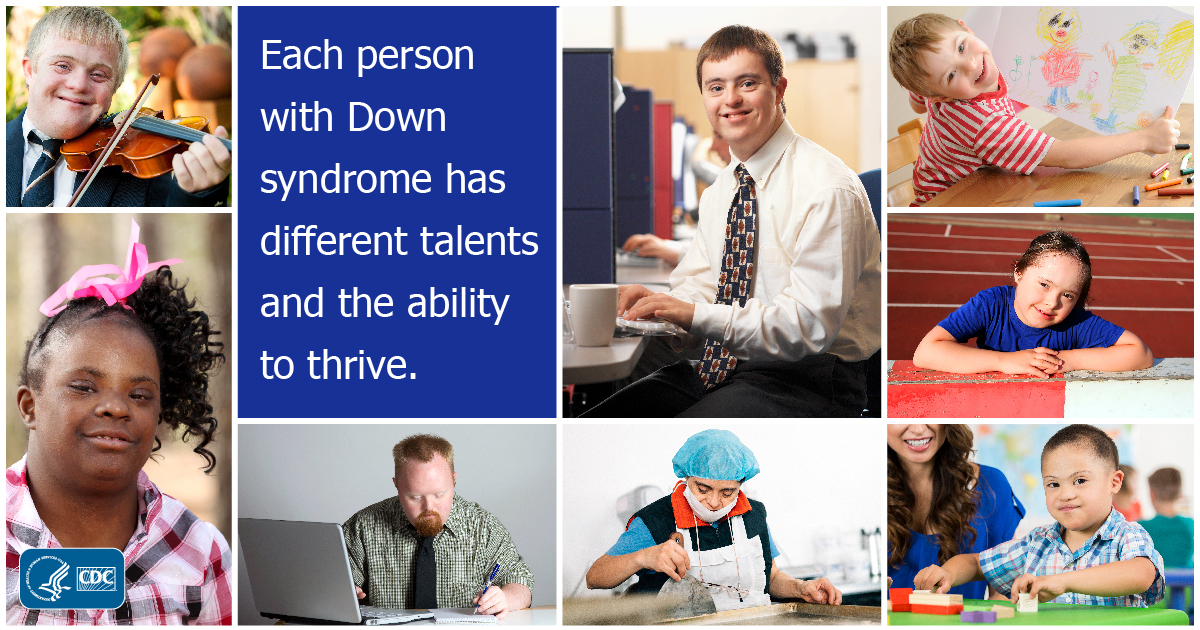

Photo from the CDC