Prenatal testing for rare disorders during pregnancy has become a routine practice for women looking to be sure their preborn baby is healthy.

But according to recent analysis provided in a comprehensive article by The New York Times, these tests are often wrong. And not just some of the time. A vast majority of the time.

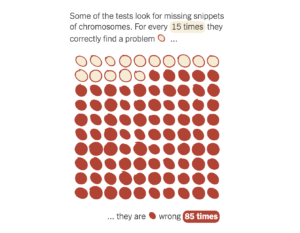

The tests check for small pieces of missing chromosomes, called microdeletions, missing chromosomes and extra chromosomes. These abnormalities cause various disabilities.

The Times examined various studies to find out how accurate the five most common microdeletion tests are and found “that positive results on those tests are incorrect about 85 percent of the time.”

Photo Credit: The New York Times

The microdeletion test for DiGeorge syndrome, which can “cause heart defects and delayed language acquisition,” has an 81% chance a positive result is incorrect.

For the disorder 1p36 deletion, which can “cause seizures, low muscle tone and intellectual disability,” there’s an 84% chance a positive result is wrong.

There is an 80% chance a positive result for Cri-du-chat syndrome, which can cause “difficult walking and delayed speech development,” is incorrect.

For Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome, which can cause “seizures, growth delays and intellectual disability,” a positive result is wrong 86% of the time.

And 93% of the time a positive test for Prader-Willi and Angelman syndromes, which can “cause seizures and an inability to control food consumption,” is incorrect.

Despite the extremely high failure rate, The Times reports that the prenatal testing industry serves “more than a third of the pregnant women in America.”

Sadly, these positive tests have likely resulted in the abortions of completely healthy preborn babies, whose tests have falsely said have disabilities.

Indeed, The Times even interviews a woman, who frantically began trying to figure out how to abort her child following an adverse prenatal diagnosis.

“‘I couldn’t help but have termination on my mind,’ said Allison Mihalich, 33, whose screening incorrectly indicated her baby might have Turner syndrome,” The Times notes.

According to the paper’s analysis, the testing for Turner syndrome is wrong 74% of the time.

Following the diagnosis, Mihalich quickly tried to arrange a follow up test before Indiana’s 22-week abortion limit kicked in for her preborn baby. Mihalich wanted the test done promptly, so if the diagnosis was confirmed, she could still have the option of aborting her baby.

Regarding another developmental disability, surveys have found that the vast majority of preborn babies diagnosed with Down syndrome are aborted. While prenatal testing for Down syndrome is far more accurate, the resulting abortions are no less tragic.

“67-85% of preborn babies diagnosed with Down syndrome are aborted in the United States,” The Daily Citizen previously reported. “In other countries, the abortion rate for Down syndrome can be as high as 90% in the United Kingdom, 98% in Denmark and 100% in Iceland.”

Down syndrome has been nearly eliminated in Iceland – but not through righteous means. It’s been eliminated by the extermination of the preborn babies diagnosed with the condition.

Focus on the Family President Jim Daly tweeted a reply to The Times’ story.

“A major story in this weekend’s @NYTimes highlights the poor track record of prenatal testing,” Daly wrote. “Parents are aborting babies based on bad test results. When it comes to the sanctity of life, trust the Lord, not companies who are profiting from fear.”

It’s a great tragedy that many babies who have been aborted because of an adverse prenatal diagnosis were in reality perfectly healthy.

But no matter what a preborn baby may be diagnosed with, each child is worthy of life and should be cared for and protected.

For more information about how to trust God following an adverse diagnosis during pregnancy, check out Focus on the Family’s Broadcast Trusting God Through an Adverse Diagnosis in Pregnancy.

In this episode, “Brandon and Brittany Buell offer hope to expectant and new parents of disabled children as they share their moving story of raising their toddler son, Jaxon, who was born with part of his skull and most of his brain missing as a result of a rare medical condition.”

Photo from Shutterstock.