The most passionate and intellectually irrepressible voice on the Supreme Court for religious liberty, the sanctity of human life, and marriage and family for the last three decades is now silent.

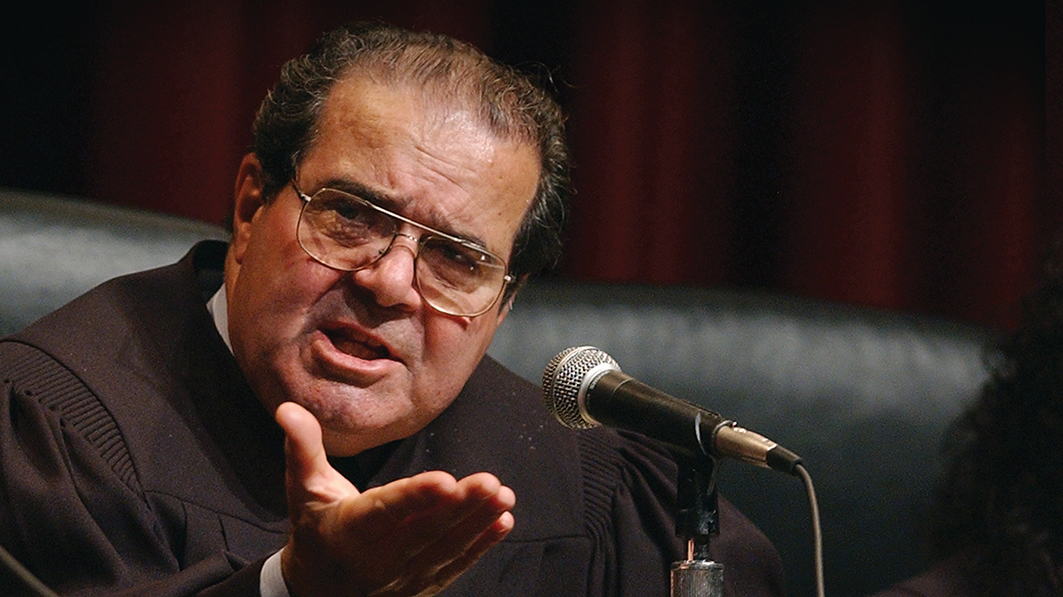

Justice Antonin Gregory Scalia, 79, died on Feb. 13, a loss of almost incalculable proportions. He embodied limitless wisdom and virtue in nearly 30 years at the high court.

One of the most influential conservatives of the last century, Scalia saw the Constitution as the embodiment of eternal precepts and was therefore rightfully wary of how bad law and poor constitutional reasoning could lead to the irretrievable loss of liberty.

From the moment Reagan nominated him to the high bench in 1986, where he won unanimous approval in the U.S. Senate, Scalia was a force to be reckoned with and an exemplar for a kind of jurisprudence considered somewhat quirky at the time—but which has come to be widely accepted as the most constitutionally orthodox manner of judging cases in America.

Called “orginalism,” Scalia believed the words of the United States Constitution’s text actually mean what they said when they were drafted and adopted by the Founding Fathers at the Constitutional Convention in 1787. The document’s fixed meaning was the lodestar for Scalia’s judgments.

The idea of a “living Constitution”—a legal document whose meaning and definitions change—amounts to legislating from the bench by mysteriously discovering rights that can’t be found in the Constitution, ultimately shaping law by fads.

Referencing a fellow justice’s opinion, he once quipped: “What is a moderate interpretation of the text? Halfway between what it really means and what you’d like it to mean?”

Instead, Scalia championed consistency in the law, infused with unmistakable depth and clarity, that was in line with James Madison and the other principle architects of the Constitution.

He was particularly dubious of using “legislative history” in deciding cases, arguing repeatedly that Congress’ role is only to make good laws within the limited, clearly defined boundaries of the Constitution. Scalia was eager and willing to strike down laws that were discordant with unwavering constitutional standards.

His impact has been so widely and deeply felt that no one in law school today, regardless of their political leanings, believes congressional mandates can be taken at face value if they violate state or local prerogatives. Even avowed “living constitutionalists” know they ignore originalism at their peril.

Scalia’s profound renewal of the proper constitutional balance between federal and state power stems from his morally courageous leadership. It was a Herculean achievement in American jurisprudence and probably his greatest legacy.

Bulwark of Freedom

Scalia often used humor to say serious things in a funny way. But in his questioning of lawyers during oral arguments and in his masterful legal opinions, he would assert there should be one unchangeable benchmark for deciding cases: Does the Constitution allow it or not?

This often made him highly unpopular on major issues when he was in the minority. But he refused to substitute emotion for thought. He had an innate distaste for conventional wisdom and nostalgia. He became famous for the elegance, clarity, biting wit and precision of his many fiery and well-reasoned dissents in some of the most important cases considered during his lifetime. His willingness to go it alone also made him a bulwark for freedom, even as some of his fellow justices were willing to impose their personal views on the rest of the country.

In 1989, Scalia bluntly wrote that Sandra Day O’Connor’s “whatever-it-takes-pro-abortion jurisprudence” simply could not “be taken seriously.” Matters on which the Constitution doesn’t force the high court to rule, Scalia believed, are for the states to decide, not nine unelected lawyers.

In dissenting on the decision to legalize sodomy in 2003 (Lawrence v. Texas), Scalia scorned the impact cultural trends too often have on the law. “Today’s opinion is the product of a court, which is the product of a law-profession culture, that has largely signed on to the so-called homosexual agenda,” he wrote, “by which I mean the agenda promoted by some homosexual activists directed at eliminating the moral opprobrium that has traditionally attached to homosexual conduct.”

Scalia predicted that case eventually would be used to redefine marriage. In 2015, his prediction came to pass—and Scalia wrote another passionate dissent. “To allow the policy question of same-sex marriage to be considered and resolved by a select, patrician, highly unrepresentative panel of nine is to violate a principle even more fundamental than no taxation without representation: no social transformation without representation,” he wrote. “The strikingly unrepresentative character of the body voting on today’s social upheaval would be irrelevant if they were functioning as judges, answering the legal question whether the American people had ever ratified a constitutional provision that was understood to proscribe the traditional definition of marriage.”

Scalia repeatedly reminded his colleagues that centralizing power in Washington will essentially create a constitution—creating something more more like a national regulatory state and less like the constitutional republic which the Framers intended.

Few things bothered Scalia more than his detractors suggesting his Christian faith was the main reason he came to some of his important legal decisions on social issues.

This was best illustrated in 2007, when a former colleague at the University of Chicago asserted that Scalia upheld the federal ban on partial-birth abortion because he was Catholic, suggesting that he was incapable of constitutional reasoning apart from his faith. Scalia told a reporter the comment was untrue and unfair, and vowed never to appear at that university until the professor had left.

Yet he utterly dismissed the concept that there should be religious neutrality in the public square. Earlier this year, he said ours is a religious republic and that faith is a central part of our national life and constitutional understanding. He said God had been generous to the United States because Americans have always honored Him.

“Unlike the other countries of the world that do not even invoke His name, we do Him honor,” Scalia noted. “There is nothing wrong with that and do not let anybody tell you that there is anything wrong with that.”

An Honorable Man

I got to know Scalia over the last 20 years in my various roles at the U.S. Senate, the White House and now Focus on the Family. I visited with him in his chambers in 2014, and he shared a story I shall never forget, told in his charming, gregarious style.

He attended Georgetown University as an undergraduate, majoring in history. At the end of his senior year, he had to appear before a small committee of the department to orally defend his thesis.

The session went marvelously until the final question, when the chairman asked, “Mr. Scalia, what is the most important event of world history?” Scalia said he didn’t remember the answer he gave—but afterward, the chairman looked at him solemnly and said, “Mr. Scalia, Georgetown has failed you if we didn’t teach you that the most important event of world history is the Incarnation of Jesus Christ.” Scalia told me he never forgot the answer to that timeless question.

Scalia will eventually be succeeded, but he can never be replaced. He was a colossus.

He was the most important and influential constitutionalist and jurist of his era. His vibrant legal reasoning and inimitable writing style were defined by their regal grace and stature. God gave him a beautiful mind and probing intellect. His categorical and clear-eyed defenses of marriage, life and conscience in the public square were matchless.

Scalia lived those principles in a long and happy marriage to Maureen, the love of his life; with their nine children and 28 grandchildren, whom he adored; and through his impact on legions of law clerks whom he credentialed to help extend the constitutional legal renaissance he started. We shall not see his like anytime soon.

How fitting that he died just two days before President’s Day, commemorating George Washington. It was somehow right that the federal government closed on the first business day after Scalia’s death, as if we were mourning and honoring the passing of a great man.

He and Washington were peers of character, leadership and a noble generosity of spirit that wreathed their consequential lives. Requiescat in pace.

Originally published in the April 2016 issue of Citizen magazine.