One of the best ways to spend the all-too-rare lazy days of summer is by reading great books. They help give families, parents, and children long-views about deep-matters in a season of the year that seems uniquely orchestrated for standing-down from the hurry-up, hurly burly-pace of contemporary life.

Summer reading should also be fun. Finding that mix among summertime books can strike the right chemistry.

I benefitted immeasurably from three new books, the first of which helped me better understand and appreciate the life and legacy of the man I consider the greatest living American, Justice Clarence Thomas.

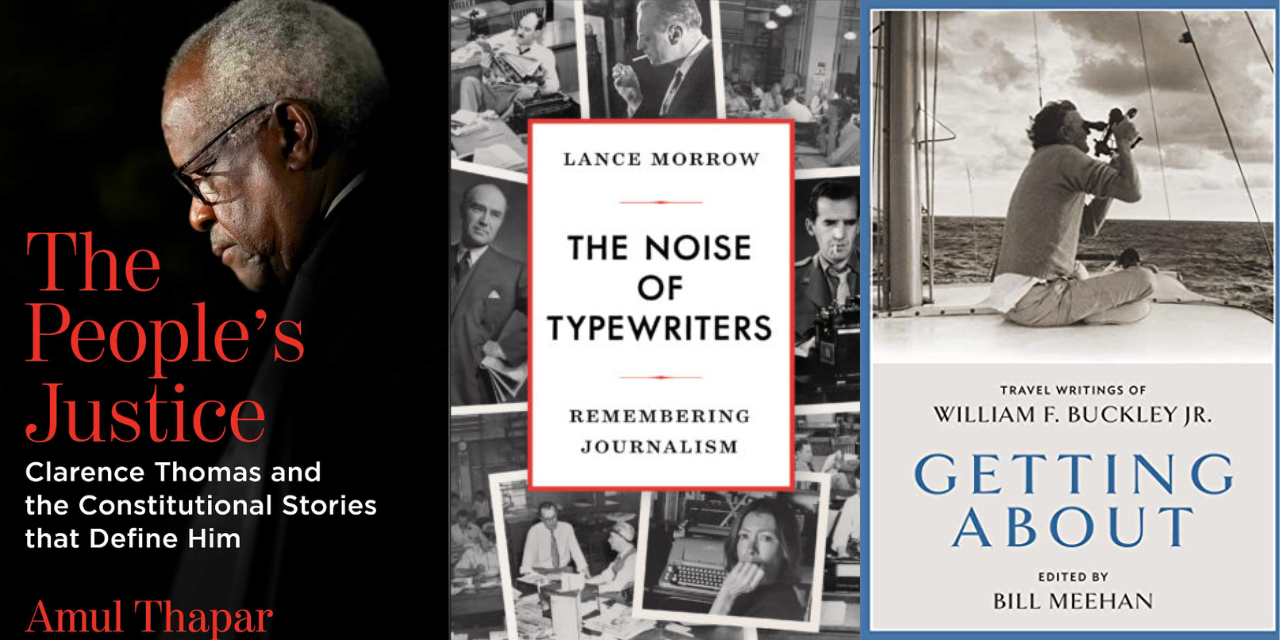

Written by a fellow jurist, Judge Amul Thapar who serves on the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals, THE PEOPLE’S JUSTICE: CLARENCE THOMAS AND THE CONSTITUTIONAL STORIES THAT DEFINE HIM (Regnery books, 2023) successfully evokes Thomas as the most constitutional originalist in our nation.

Thapar’s unique vantage-view from the bench helps demonstrate the brilliance of Thomas’ reasoning and his firm commitment to not being side-tracked or influenced by fashionable legal theories. Thapar’s own jurisprudence is in sync with Thomas’, and therefore helps the reader better understand why certain cases are decided in the manner they are.

If I had to select and recommend a single book that successfully gives the reader a deep-plunge into how Thomas navigates the highest echelons of American law, this is the volume I would recommend. It crackles with the power of great ideas, and it reveals a Supreme Court justice who, in the best tradition of our highest court, has perfected the gift of disinterestedness — always finding ways of applying the timeless principles of our Founders to the most pressing legal cases of our era.

Thapar demonstrates the Thomas pattern of identifying the Constitutional principle at stake, case by case, and then applying that principle in a manner that happily leaves fashionable trends and ‘living constitutionalism’ aside, and instead championing the application of the unchanging meaning of the words in the Constitution to the case at hand.

I especially appreciated that Thapar does not attempt to be wide-ranging in his review of the Thomas legacy but rather focuses, with an enviable jeweler-like precision, on a dozen cases and the litigants who are directly impacted in those cases. This is a difficult task because the author seeks to more fully allow us to understand the litigants in these cases without sacrificing the principles on which their cases fall or rise.

What I mean is that, in our emotion-drenched era, it is easy to feel deep-sympathy with these litigants even if they do not deserve to prevail.

Thomas has written, “Finding the right answer is often the least difficult problem” and says a justice must find “the courage to assert that answer and stand firm in the face of the constant winds of protest and criticism.”

If any jurist in America has lived up to that matchlessly high standard, it is Thomas himself.

Attaining the highest legal standards in American law is not the only apogee to be reached among the three books under consideration. So are new books by two of America’s most consequential journalists of the last century.

Each of these books is a kind of lyrical gem, and it makes it all the more special that before the death of one of the two, they were good friends who esteemed each other’s work even if they did not always agree on the most cutting-edge issues of the era in which they were doing their most important consequential reporting and commentary.

How fondly I recall — as a young boy growing up in Fort Wayne, Indiana — the weekly arrival in our postbox of the red-bordered TIME magazine. Beginning when I was in fifth grade, I became a faithful and avid reader even if I did not always understand all that was being covered and analyzed.

I loved to look at and study the cover of TIME week by week, and then to read each of the special sections of the magazine, as if the entire world could be divided up and assigned a section: International, National, Sports, Entertainment, etc. TIME sought to make sense of the world, and a colossal reason for its success was its multi-talented pool of writers and correspondents.

My favorite TIME writer was, without any equal, Lance Morrow whose prose sparkled and glittered; whose intelligence was worn-lightly but not meekly; and whose undoubted conviction about the biggest stories of the week was never in doubt even as his prose-style was animated by fair-play and a rare, uncommon grace among the most important journalists of his time.

Morrow’s superb memoir THE NOISE OF TYPEWRITERS: REMEMBERING JOURNALISM (Encounter Books, 2023) is such a fun and jaunty ride that the reader is loathe to put it down even for a moment.

Inside these pages are all the major public policy figures of the last 75 years, many of whom Morrow knew personally.

Morrow’s memoir reads like a drama on the stage only it’s an autobiography between hard covers, and always with an especial doff of the hat to Henry Luce, the founder and genius behind TIME INC., whose magazines were the thoroughbreds of American journalism: TIME, LIFE, SPORTS ILLUSTRATED, FORTUNE, etc.

Morrow shows us how Luce’s week-by-week vision for his magazines was rooted in American exceptionalism, and why in Luce’s view the 20th century could only rightly be defined as The American Century.

It matters deeply to Morrow that Luce’s upbringing, family, and worldview were synonymous with and shaped by an unremitting missionary zeal and confidence, and Morrow convincingly demonstrates that TIME was indeed the most important journalistic pace-setter not only among the power-class in America but also among average citizens from coast to coast who felt a deep commitment to the Luce publications as comprising the most important, thoughtful, accurate journalism nationwide.

When did that era end?

Morrow closes his memoir by elegiacally describing how he felt departing Radio City Music Hall in New York City after TIME’s 75th anniversary party, knowing that the world and American journalism had shifted drastically:

“After it was over, I walked out through the glass doors onto Sixth Avenue, and I looked up at the Time-Life Building across the way, its offices mostly dark now. I watched John Kennedy Jr. walk away briskly, heading north in the cold and rain. It occurred to me that the twentieth century had gotten old. That night, it was almost exactly one hundred years since Henry Luce had been born in a Presbyterian mission in China while, at the same moment, on the other side of the world, [publisher] William Randolph Hearst’s newspapers, with a fine sense of publicity and frolic, stirred up the Spanish-American War. Selah.”

Morrow’s friend and fellow journalist William F. Buckley Jr., the founder of the blue-bordered NATIONAL REVIEW magazine, only makes a small, cameo appearance in the memoir but that is ok because some of the best of Buckley’s travel writing oeuvre comprises a new compendium GETTING ABOUT: TRAVEL WRITINGS OF WILLIAM F. BUCKLEY JR. edited by Bill Meehan (Encounter Books, 2023).

This collection has been adroitly chosen and expertly chosen, so much so that a reader could be forgiven for forgoing actual travel himself or herself and merely sitting in his or her favorite summer chair and absorbing Buckley’s incomparably witty, eloquent, elegant, and lively observations from every point on the globe.

Buckley’s unflappable style is so meticulous that, chapter by chapter, the reader feels he has been with him on the airplane; on the sailboat; on the railroad; on the sea; above the clouds; and feeling a sometimes-euphoric mix of speed and joy that, in traveling through these essays, you feel you are riding in that gear above top gear, overdrive.

It is the perfect summer-read because Buckley is the perfect travel companion, raising friendship to an artform which comes through so powerfully in his travel writing, page-over-page.

I had the privilege of sailing with him many times. I will never forget one of our most memorable sails together from the Stamford, Connecticut, docks into the Long Island Sound on our way to Oyster Bay, New York.

The wind was just right, and the sails were beautiful against the emerging sunset. The clouds folded back; the twinkling stars emerged as if on cue; the Manhattan skyline was clearly visible and shining out of the near-darkness.

The mast, the sails, the retreating clouds, the dark water: There was an intensity bordering on grandeur which was an epiphany and sublime.

We sailed across into Oyster Bay (“Fitzgerald and Roosevelt territory,” I remember Bill saying), with Bach’s music playing during most of our trip across the Sound. The whole evening seemed serendipitous.

A sumptuous dinner followed, and then the oncoming chilly summer evening on the waters of the Atlantic in the midst of the Eastern seaboard, all the while fresh air pouring into the boat’s cabin as we slept that night, with the only sound of waves lapping against the boat during the night.

Bliss.