At the height of COVID-19, prognosticators spanning the spectrum from physicians to politicians predicted the death of the handshake. For a time, the age-old gesture gave way to fist and elbow bumps and salutes and wider smiles – but not for long.

Thankfully, the handshake is back, and not a minute too soon. In a deeply divisive and chronically agitated age, it’s difficult to overestimate the value of pressing the flesh in a symbolic act of goodwill.

Dating back thousands of years, most historians trace the handshake’s origin to its practical and peaceful intent of demonstrating the shakers weren’t carrying any weapons. The Quakers are said to have popularized it as part of regular greeting. That’s not surprising given the denomination’s emphasis on peace.

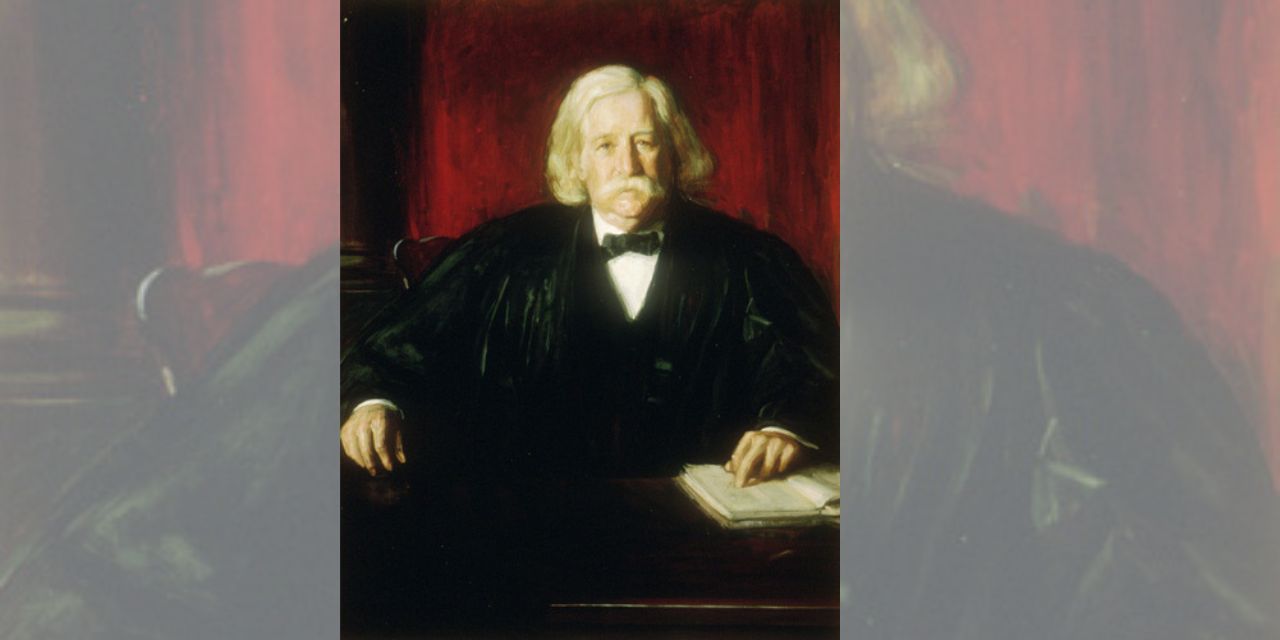

Melville Weston Fuller, the eighth chief justice of the United States Supreme Court, wasn’t a Quaker (he was known to worship at an Episcopal church), but he did feel strongly about shaking hands. In fact, Chief Justice Fuller is credited with implementing the “Judicial Handshake” at the High Court, where he served for 22 years until his death on Independence Day of 1910.

Much has been written of late about the supposed politicization and criticism of the Supreme Court, but it may or may not surprise you to learn that the justices incurred plenty of criticism back in Chief Justice Fuller’s era too.

Despite stark differences of judicial philosophy, the Chief Justice, known for his good manners and courtesy to all, was determined to maintain unity and collegiality among the nine justices. Fuller decided one way to help forge such harmony and civility was to have all the judges shake hands before assembling on the Bench or commencing their private Conference meetings.

Chief Justice Fuller rightly understood that it’s a whole lot more difficult to be rude to someone if you’ve just shaken hands with them.

That same tradition at the Supreme Court persists to this day.

Disagreeing without being disagreeable is more art than science, but it’s a foreign concept to many, especially elected representatives in Washington. As it is now, representatives are often speaking to C-SPAN or cable news cameras, and more empty than full seats when they stand to make a speech. Civility and decorum isn’t always their priority, but it is important.

How different might the tone and tenor be in the United States Congress, though, if members of the House and Senate were required to shake hands with one another before the beginning of each day? You might be thinking such a suggestion is impractical. Shaking hands with eight other justices is easier and quicker than with 434 in the House or 99 in the Senate – but what if they started with just ten or twenty? Little by little, a little becomes a lot. It would be time well spent.

Civility doesn’t equate to compromise or agreement. The Supreme Court rightly remains deeply divided on an ideological basis, but they’ve been historically polite and magnanimous to one another in the process. The “Judicial Handshake” contributes to such a climate. The same would be true in Congress.

“The handshake of the host affects the taste of the roast,” quipped Benjamin Franklin. The same might be said of the United States. Our elected representatives serve as the nation’s hosts, which may explain why the metaphorical roasts we’re being served aren’t tasting too good lately.

Image Credit: United States Supreme Court Collection