Why Did Justice Thomas Vote Against the Cheerleader’s Free Speech?

The U.S. Supreme Court decided earlier this week by an 8-1 majority that a public high school could not discipline a student for her profane Snapchat criticism of the school, its cheerleading squad and softball program after she failed to be selected for the positions she wanted. As The Daily Citizen explained, the majority felt that a government entity – the public school – through its cheerleading coach wrongly infringed the girl’s free speech rights for something she said outside of school and after school hours.

As you may have guessed from this article’s title, Justice Clarence Thomas was the lone dissenter in that case. Thomas has long been one of the high court’s most ardent originalists – judges who look to the text and original understanding of the Constitution and statutes they interpret – along with the late Justice Antonin Scalia, so at first blush it’s a little shocking to see Thomas apparently voting against free speech. Conservatives hold him in such high regard that it’s worth taking a look at this case from Thomas’ point of view, because there are always nuggets of wisdom to be gained from doing so.

First, Thomas insists that the majority is missing or avoiding the entire history of the doctrine of in loco parentis, a legal term that means that public schools stand in the shoes of the students’ parents when in school. That means school discipline can be enforced because the parents are not there to do it themselves. The question this case asks is, “When does that authority extend beyond the school’s premises?”

“The Court overrides that [cheerleading coach’s disciplinary] decision—without even mentioning the 150 years of history supporting the coach,” Thomas wrote. “Using broad brushstrokes, the majority outlines the scope of school authority. When students are on campus, the majority says, schools have authority in loco parentis—that is, as substitutes of parents—to discipline speech and conduct. Off campus, the authority of schools is somewhat less. At that level of generality, I agree.

“But the majority omits important detail. What authority does a school have when it operates in loco parentis? How much less authority do schools have over off-campus speech and conduct? And how does a court decide if speech is on or off campus? Disregarding these important issues, the majority simply posits three vague considerations and reaches an outcome.”

To understand Thomas’ next piece of analysis, we have to explore a little history of free speech, the Constitution, and state schools.

The First Amendment’s free speech provisions didn’t always apply to states and their public schools. When ratified in 1791, it bound only Congress and the federal government. After the 14th Amendment was adopted following the Civil War, banning states from infringing the civil rights of the nation’s African Americans, the Supreme Court gradually began “incorporating” other federal constitutional rights that states would be held to, including the freedom of speech.

So, Thomas takes an originalist approach by looking at the general understanding of the scope of a school’s authority over its students at the time the 14th Amendment was passed. That’s a typical feature of a Thomas judicial opinion.

And after noting that schools had wide authority to discipline students for actions and speech while at the school, he observes that, “[A]lthough schools had less authority after a student returned home, it was well settled that they still could discipline students for off-campus speech or conduct that had a proximate tendency to harm the school environment.”

The historical examples he cited include disciplining students for disrespecting a teacher, examples of which fill the casebooks of the nation’s courts. Thomas asked his fellow justices why they seemingly ignored this history in reaching their decision.

Next Thomas addressed the historical scope of in loco parentis. The established doctrine, unless the court chooses to moderate it, says Thomas, is comprehensively protective of the schools. “The doctrine of in loco parentis limited the ability of schools to set rules and control their classrooms in almost no way,” he wrote, citing another Supreme Court decision about school discipline, Morse v. Frederick, the famous “Bong Hits 4 Jesus” case. In the Morse case, the court upheld the school’s right to discipline a student for displaying a sign promoting the use of illegal drugs at a school-supervised outing to witness the Olympic torch relay passing nearby.

Although there are plausible arguments for revisiting the boundaries of in loco parentis, the majority skipped over it entirely, Thomas argued. If the court has chosen not to revisit the longstanding parameters of the doctrine, then it is forced to implement it as it stands. And this, Thomas says, the majority failed to do.

Finally, Thomas addressed three factors present in the cheerleader’s situation that make it different from the court’s landmark student free speech decision in Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District, a 1969 case that the majority relied on to analyze this cheerleader’s speech.

- This cheerleader’s speech is about an extracurricular activity, outside the classroom, whereas Tinker’s symbolic speech was about wearing a black armband to school to protest the Vietnam War. History suggests that a school’s authority over speech is greater when it concerns extracurricular activities.

- The use of social media has the capability to cause more harm than in-person speech, not less, because more people become aware of it faster.

- Was the cheerleader’s speech truly “off campus?” Speech travels, Thomas notes, and no one would question whether the school could punish someone for bringing onto school premises copies of a flyer containing vulgar language similar to what the cheerleader said on Snapchat. It’s a tricky question, Thomas says, but one that can be resolved. “But where it is foreseeable and likely that speech will travel onto campus, a school has a stronger claim to treating the speech as on-campus speech,” he wrote.

Thomas concluded that the cheerleader’s speech should be treated as on-campus speech, and that being the case, her resulting discipline fell within the scope of the in loco parentis doctrine.

If nothing else, Justice Thomas’ thorough dissent is worth understanding because of his strong desire to hold his fellow justices to a rigorous examination of the legal principles they rely on to reach the decisions they do. That’s the type of judicial discipline he holds himself to, and one for which conservatives have been incredibly grateful over the years.

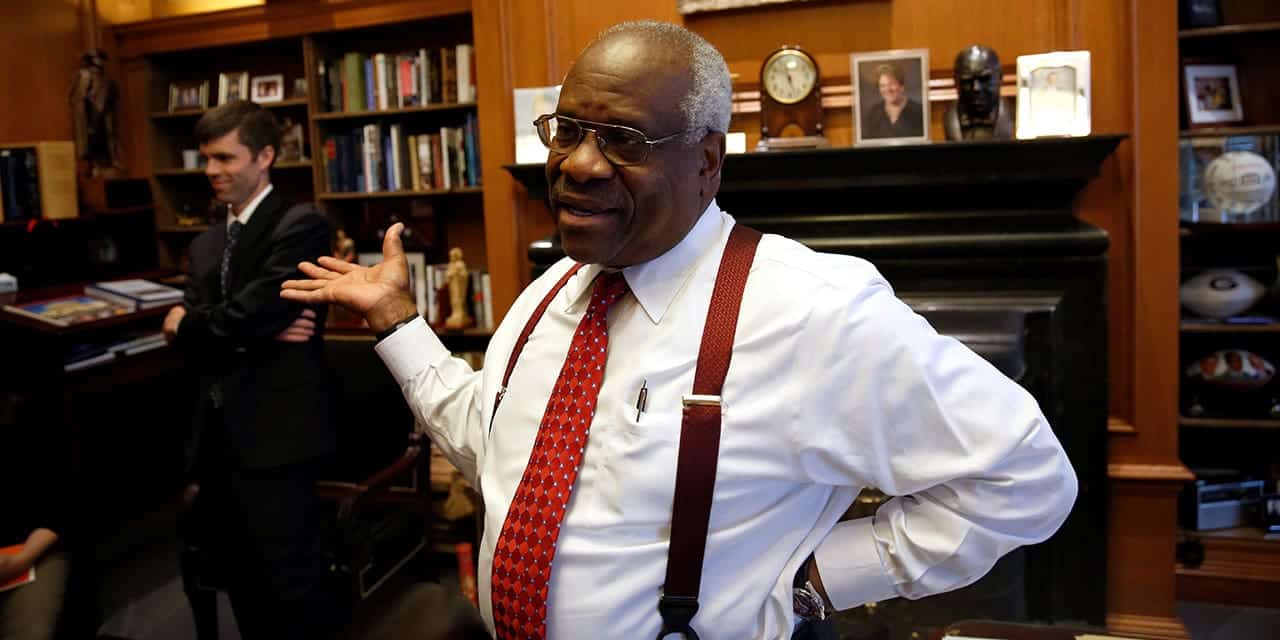

Photo from Jonathan Ernst/REUTERS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Bruce Hausknecht, J.D., is an attorney who serves as Focus on the Family’s judicial analyst. He is responsible for research and analysis of legal and judicial issues related to Christians and the institution of the family, including First Amendment freedom of religion and free speech issues, judicial activism, marriage, homosexuality and pro-life matters. He also tracks legislation and laws affecting these issues. Prior to joining Focus in 2004, Hausknecht practiced law for 17 years in construction litigation and as an associate general counsel for a large ministry in Virginia. He was also an associate pastor at a church in Colorado Springs for seven years, primarily in worship music ministry. Hausknecht has provided legal analysis and commentary for top media outlets including CNN, ABC News, NBC News, CBS Radio, The New York Times, the Chicago Tribune, The Washington Post, The Washington Times, the Associated Press, the Los Angeles Times, The Wall Street Journal, the Boston Globe and BBC radio. He’s also a regular contributor to The Daily Citizen. He earned a bachelor’s degree in history from the University of Illinois and his J.D. from Northwestern University School of Law. Hausknecht has been married since 1981 and has three adult children, as well as three adorable grandkids. In his free time, Hausknecht loves getting creative with his camera and capturing stunning photographs of his adopted state of Colorado.