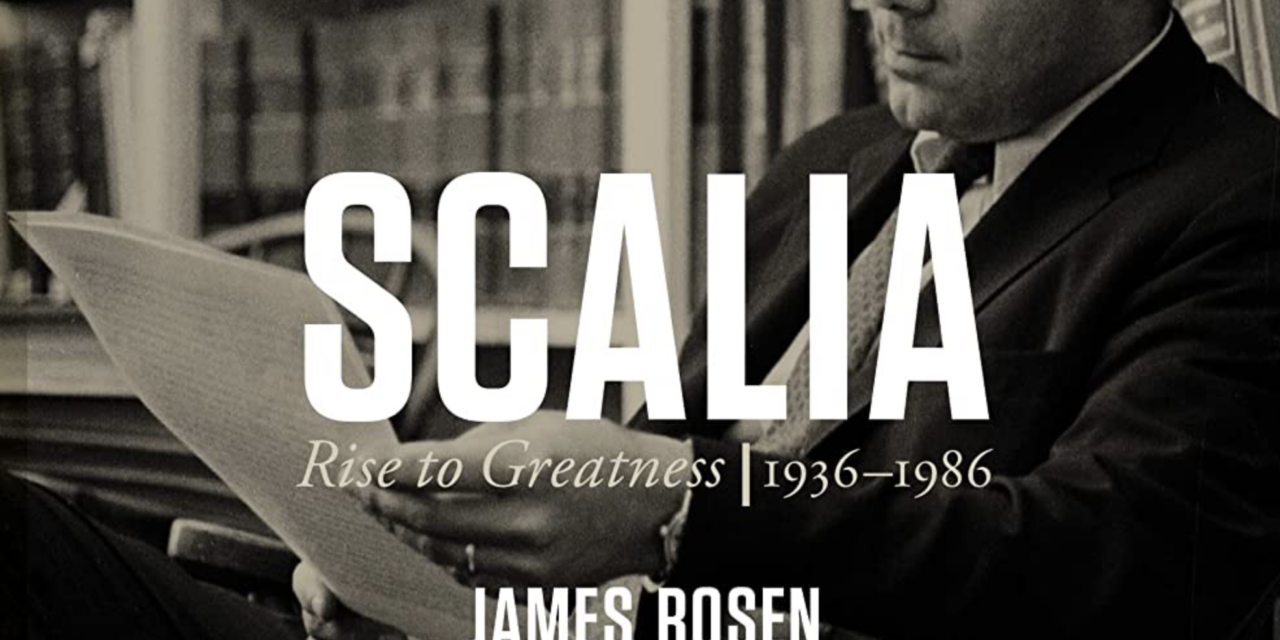

My friend James Rosen has marvelously captured the late, great Justice Antonin Scalia in his wonderful new biography SCALIA: RISE TO GREATNESS 1936-1986 (Regnery Books, 2023).

The book is so vivid and timely that the reader feels right from the start as if he has joined a journey or pilgrimage wending toward some kind of grand arrival or validation in the public square.

The sheer eloquence and deep research of the book echoes Scalia’s own such commitments to excellence, and along the way we get to know with sparkling engagement and definitiveness the brilliant manner and route in which one of the most talented, gifted writers and jurists ever to sit on the high court actually got there.

What I particularly loved about the book is that, when finished, I felt as if I genuinely understood how Scalia got to be Scalia — the people, chapters, and vicissitudes of his otherwise busy-life all pouring into the shaping, impacting, and molding of the making of a great American legacy.

This is the best kind of biographical history: fact-based, not-ideological, and willing to tell the truth about the course and nature of human ambition and the application of both power and influence which are not the same thing even though often used interchangeably.

Rosen writes with a brio and crackling energy that is almost tangible, and his personal style carries you along.

He lyrically deduces from the justice’s first 50 years not only everything important about the structure and architecture of ascent to the DC Circuit Court of Appeals and eventually the Supreme Court – star student, life in New York and New Jersey, the ambiance of growing up in a midcentury Italian subculture, Georgetown, Harvard Law, marriage to Maureen (she of Radcliffe), nine children – but also Rosen rightly places the late justice’s Christianity at the center of what unfolds layer by layer, as if a multifoliate rose.

This is a biography of nuance and ballast: the child known as Nino; loving and supportive parents; a brilliant student whose sense of confidence is deep and wide as oceans; setbacks here and there in often unexpected and complicated ways; the balancing of family and work; teaching law and the founding of the Federalist Society, a gift for navigating Washington DC and its diffuse power structure; the selection and nomination by President Ronald Reagan to a seat on the Supreme Court; and the unanimous vote of confirmation in the Senate. All of it is fascinating and even riveting, packed into 400+ pages, and with a second volume ahead.

Yet for all the welcomed-details and hairpin curves, what is best about this biography is that the golden narrative does not miss at any remove Scalia’s two major animating commitments beyond family: his deep and profound faith in God, and his unwavering fidelity to the United States Constitution. The latter commitment made him probably the most famous originalist in American history, and the seedlings of that tenacious jurisprudence, for all that would follow on the high court, have been planted beautifully in this biography.

But it is the former commitment, to Scalia’s profound and personal faith, that I particularly enjoyed reading and learning about. Time and again, I was struck by the centrality of his Catholicism and the subsequent timeless and personal honor code that was shaped by it.

I remember a famous interview the justice did late in his life in which the topic of the reality of the devil came up. The journalist asking the questions of Scalia seemed semi-surprised that Scalia actually believed in a literal devil, while Scalia expressed mild-amusement that the journalist seemed not to understand that the overwhelming majority of Americans believed in the devil — just as he did. This kind of authenticity of faith is a revelatory pillar in Rosen’s fine book.

I came away certain that it would be impossible to understand Scalia without understanding his faith, and Rosen has succeeded in evoking that faith in a manner subtle, supple, and nimble in a way rarely achieved in biographies about famous Americans. Too often, faith gets a short shrift. Not here.

It brought to mind one of the most beautiful eulogies I have ever been honored to hear: the one delivered by his son Father Paul Scalia at the Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington DC for his father:

“We are gathered here because of one man. A man known personally to many of us, known only by reputation to even more. A man loved by many, scored by others. A man known for great controversy, and for great compassion. That man, of course, is Jesus of Nazareth.”

Father Scalia was humbly reminding us that Christ and faith were the center of his father’s life, and not the things of this world — fascinating and marvelous though they may be. The trappings of the court did not change Scalia; he changed it and its reputation.

Rosen in his fine biography makes the same distinction, earning the late Justice Scalia his perfect biographer.