The COVID-19 pandemic brought to the forefront of millions of minds something most people don’t like to consider: death. Lockdowns, facemasks, vaccines, social distancing and church closures all served, ostensibly, as an attempt to prevent people from dying from a deadly virus.

The hundreds of thousands of deaths attributed to COVID-19 in the United States is a great tragedy. And yet, every life-saving measure, procedure, therapeutic or vaccine given within the last year and a half really isn’t “life-saving.” In actuality, these things are only “death-delaying.” We will all die someday.

In his most recent book Things Worth Dying For, Archbishop Emeritus Charles J. Chaput examines those things that are worth dying for.

The archbishop posits, “It’s a good thing, a vital thing, to ask what we’re willing to die for. What do we love more than life? To even pose that question is an act of rebellion against a loveless age.”

“And to answer it with conviction is to become a revolutionary; the kind of loving revolutionary who – with God’s help – will someday redeem a late-modern West that can no longer imagine anything worth dying for, and thus, in the long run, anything worth living for.”

He explains that appropriately and moderately considering one’s own death is a healthy thing. For only by pondering what we would die for, can we consider what we should live for.

Archbishop Chaput adds, “There are two great temptations that I’ve seen people struggle with over my lifetime. The first is to try to create life’s meaning for themselves, which translates in the end to no meaning at all.”

“The second is to live and die for the wrong meaning, the wrong cause, the wrong purpose. The world is full of disguised and treasonous little gods that demand our full attention and, in the end, betray our deepest longings.”

The late Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, himself a man of faith, made a similar observation in a speech he delivered at his son Paul’s graduation ceremony in 1988.

Compiled in the book Scalia Speaks, the justice said, “It is a belief that seems particularly to beset modern society that believing deeply in something, and following that belief, is the most important thing a person can do.”

“I am here to tell you that it is much less important how committed you are than what you are committed to.”

So, as Christians, what should we be committed to? What is worth dying for?

Faith

Among other answers to the above two questions that Archbishop Chaput gives, is faith.

“If we value a thing highly enough, we’ll be willing to die for it. For many people throughout history and still to this day, the Church and the faith she teachers are, taken together, the greatest such precious thing.”

The archbishop notes that Christians from other countries are faced daily with the question of whether they will be willing to give their life for their faith.

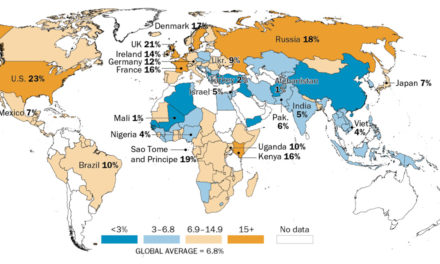

“As I typed these words in the spring of 2020, Christians were dying by the hundreds in Nigeria at the hands of Islamist murderers. In China, North Korea, Vietnam, India, and much of the Islamic world … Christians endure harassment, discrimination, and violence simply because of their faith.”

“Christians are now the most widely persecuted religious group on the planet,” he notes.

But for decades, it has been immensely easy to be a Christian in the United States. We don’t face the daily threat of violence that many other Christians do.

And yet, the tide seems to be slowly turning, as Christians in the United States are being required to stand up for their faith. The Daily Citizen chronicled numerous examples of churches being forced to be closed during the pandemic last year.

“The United States has always been a good place for religious believers,” Archbishop Chaput writes. “In the future, that may not be so.”

Christians would do well to consider what sacrifices may be required to remain a faithful Christian in America in the coming decades.

Family

“Throughout history, people have lived, worked, and died to nourish and protect their families. And for good reason. The family, rooted in the fertile differences between the sexes, is a cornerstone of human identity,” the archbishop writes in a chapter on family, called, “The Ties That Bind.”

“It’s a deep source of security and personal meaning. It gives each of us a home and a role in the world that links past generations to the future.”

However, the family is under attack from four directions, he writes. These include:

- “Our political system itself … A subtle distrust of marriage and the family, which are always filled with unforeseen duties, is … hardwired into democracy’s DNA.”

- Economic realities. “Globalization has served America’s wealthy top tier quite well. But as lower-skilled jobs disappear, middle- and working-class wages have stagnated – or, worse, declined. This often forces both parents out of the home and into the workforce, disrupting family life. It also keeps many families from saving even for emergencies.”

- “The unintended effect of scientific and technological advances … Concern for electronic diversions and their impact on the mental health and development of children is now widespread.”

- “Hostility to the idea of the family itself – mother, father, children, and extended relations – is a unique mark of the modern era.”

Ultimately, though raising a family is particularly hard in modern society, these social ties bind us so tightly that “humans will live and work and, when needed, die to have their families flourish.”

Faith and family are two areas where Christians can find meaning, purpose, and love. Love for God and love for each other.

These two ties are truly worthy dying, and living, for.

One of the main goals of Focus on the Family is to strengthen these “ties that bind.” Focus on the Family provides free, one-time counseling consultations with a licensed or pastoral counselor. If you would like to request one, you can call 1-855-771-HELP or fill out a Counseling Consultation Request Form here.

You can follow this author on Parler @ZacharyMettler

Photo from Macmillan