In some ways, what happened in Sturgis, S.D., in the first week of August last year was the same thing that happens every year about that time: Hundreds of thousands of bikers roared into town for the annual Sturgis Motorcycle Rally in the beautiful Black Hills area, an hour’s drive from Mount Rushmore.

But this time, some things were different.

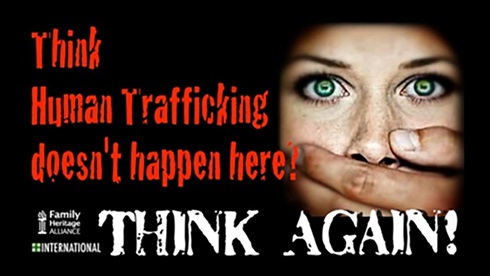

Cyclists approaching town on I-90 or Highway 16 couldn’t help noticing the big, eye-catching billboards around Rapid City, depicting girls who’d implicitly been abducted and the message: “Think Human Trafficking Doesn’t Happen Here? Think Again!” At the top of the billboards was the toll-free phone number of the National Human Trafficking Hotline.

Once they reached the rally, many bikers encountered volunteers who circulated through the crowd, handing out thousands of baseball cards which featured photos not of athletes, but of young girls who were missing and potentially present in Sturgis—at risk of being found and exploited by traffickers, if they hadn’t been already.

The bikers had a powerful reaction, says Dale Bartscher, one of the people behind the anti-trafficking campaign.

“When our volunteers handed the bikers these cards, the Number One statement they heard was, ‘(Law enforcement) had better get their hands on this guy before I do,’ ” Bartscher tells Citizen. “That was the overwhelming heart of those who came to the rally. They were extremely helpful, and alerted law enforcement when they saw someone who looked like one of our cards.”

That response was deeply gratifying to Bartscher, a longtime pastor and executive director of the Family Heritage Alliance (FHA) in Rapid City, a public-policy partner of Focus on the Family. For the past few years, he’s been a central figure in South Dakota’s energetic drive to stop modern-day slavery and sexual abuse.

Bartscher is all too familiar with the numbers pointing to the appalling scale of human trafficking. According to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, an estimated 100,000 American youth are forced or lured into prostitution each year—starting at an average age of 13 or 14—and 300,000 are at risk.

“It’s a national and worldwide phenomenon,” he says, “And it’s in our back yard here in South Dakota.”

Though the state is lightly populated, Bartscher says it has attractions for those engaged in the flesh trade: Its interstates, its truck stops, its hunting lodges—all places that draw transients. Its Native American reservations, where kids are easily victimized. And the Sturgis rally—where the vast majority of attendees are law-abiding, but where the sheer size of the event creates an optimal hunting ground for those who would exploit children.

“The industry knows who to target,” Bartscher says. “The homeless, poor single moms, runaways. Kids with a drug addiction, single parents or no parents. Kids who’ve been abused. Kids who aren’t careful, who are just looking for an adventure.”

In short, the targets are the most vulnerable people in society—the very people FHA is devoted to protecting.

“Our mission statement says we want South Dakota to be a state where God is honored, religious freedom flourishes, families thrive and life is cherished,” Bartscher says. “We can’t put human trafficking and its consequences on our back burner. It’s got to be on our front burner.”

‘Somebody’ Means ‘Us’

Ask Bartscher how FHA got heavily involved in fighting trafficking, and he’ll give you a name: Scott Craig.

Craig wears many hats: He’s a pastor, a state representative, a Tae Kwon Do instructor. He’s also a member of FHA’s board of directors. And he brought his commitment to the cause to the organization.

“Scott instructed us, he informed us—and he inspired us,” Bartscher says.

Though he has lived in South Dakota since 2009, Craig’s passion for this issue began while serving at a church in Hawaii, a state which is a way-station for the international slave trade. He’s met girls who’ve been victimized by it. And he’s haunted by them.

“They are the most damaged human beings on the earth,” he says, pausing at length before he can go on. “These girls mostly wish they’d never been born. They’ve been lured, drugged, beaten, broken of their will, their resistance, all so they can service as many as 30 to 50 perverted, violent men a day. A day.

“They’re used raw. They don’t want to be touched. They don’t want to be hugged. The response of someone who rescues them is, ‘We want to wrap them up in our arms.’ They don’t want that. They want to be left alone. They want distance, if not death.

“What these girls are thinking and feeling—it’s beyond description. Somebody has to put a stop to it.”

The more they spoke with Craig, the more Bartscher and the FHA team found a conviction growing within them: “Somebody” means “us.”

In the meantime, a woman named Tess Franzen had developed the same conviction. Hoping to start a ministry to the victims, she reached out to Bartscher for help.

“It doesn’t make sense to start a ministry in South Dakota without talking to Dale; he’s so well connected,” Franzen tells Citizen. “We spoke for about 90 minutes, and then he asked if I’d come on board as director of their new human-rights division.”

Franzen started the job in April 2013, promoting awareness of trafficking in the media as well as in churches, and finding a strong public interest in the issue. Beyond that, though, she and Bartscher realized that to be effective, they needed to build a large network of groups striving toward a common goal.

So they did. FHA gave birth to the West River Human Trafficking Task Force, with 33 members representing public and private agencies from the federal to the local level.

“We have every level of law enforcement—Homeland Security, state attorney general, U.S. attorney, FBI, local law enforcement—working along with social-service agencies and groups like homeless shelters, women’s shelters, child care, ministry leaders,” Franzen says. “It’s a great group, a very diverse group.”

And a very cooperative group, says Pennington County Sheriff Kevin Thom. “Everyone brings something different to the table and has something different to offer,” he tells Citizen. “There are things we can do and things private groups can do better. For example, Dale and his people were able to raise money to put up those billboards; that’s more practical for them than through government bureaucratic channels.

“It’s invaluable—the collaborative efforts, the partnerships,” Thom adds. “Without them, we can’t do our job. It’s different from some parts of the country where agencies don’t play well together. We have good relationships with all the groups.”

Preemptive Strikes

South Dakota’s U.S. attorney, Brendan Johnson, has pursued traffickers energetically, bringing 31 human-trafficking cases to court in six years and winning more life sentences for trafficking than in any other state.

“He’s very passionate about this issue,” Franzen says.

Similarly, South Dakota’s attorney general, Marty Jackley, has taken up the cause. His office has worked with other agencies—city and county—to launch five sting operations in the past two years.

“We wanted the bad guys caught before they harm a child,” Jackley tells Citizen. Thus, officers pose online as potential victims, luring traffickers into the open. The results have been impressive: The stings have led to 19 arrests—including nine in 2013 and six in 2014 at the Sturgis bike rally—and most have led to convictions.

“We’ve made many arrests,” Jackley says. “Often we find they’re out-of-state people preying on our children. Our numbers look significant, but it’s because of the approach we’ve taken: We put a stop to it before children are harmed.”

Jackley has also been assertive on the legislative front, urging that law enforcement be given the tools to fight trafficking more effectively. Last year, a new state law provided a way for the state to seize the assets of convicted traffickers. This year, a bill requiring them to register as sex offenders has passed the Senate and, at press time, seemed certain to sail through the House.

Like Thom, the attorney general stresses that fighting trafficking is a public-private partnership—and he’s thankful for the role groups like FHA play.

“The Family Heritage Alliance and Dale Bartscher have been absolutely wonderful, both in supporting our legislation and spreading awareness,” he says. “The faith-based community makes a huge difference. They have an ability to expand their reach through prevention talks, helping shelters, volunteering. They’re a huge resource to fight child abuse.”

Seldom has the value of partnership been clearer than when trying to get the word out about trafficking for the 2014 Sturgis Motorcycle Rally.

“We didn’t have a huge budget,” Franzen says. “We’re a ministry, and we have to be very careful with the money people donate.” So she sought out prominent South Dakota officials to record free public-service announcements, focusing on three who’d been especially active on this issue: Jackley, Johnson and U.S. Rep. Kristi Noem, who was promoting anti-trafficking legislation on the federal level. All three readily agreed.

That freed up resources to pay for two large billboards near Rapid City, not far from Sturgis—a visual tool to spread awareness that would be supplemented when a Rapid City advertising company supplied seven more electronic billboards for just a token fee.

FHA also found valuable allies in anti-trafficking groups, both in and out of the state. Their billboards were designed free of charge by F.R.E.E. (Find, Rescue, Embrace and Empower) International, a Las Vegas-based organization which partners with public and private agencies to fight the worldwide slave trade. F.R.E.E. also worked with other groups (KlaasKids, Called2Rescue, the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children) to prepare a book of missing children who might be in South Dakota, and to put some of their pictures on baseball cards.

“That’s what makes this work,” Bartscher says. “It’s not just one group. It’s law enforcement coming alongside the church coming alongside agencies and groups that care about children. It’s taken a lot of energy and a lot of working together.”

‘No More’

Fortunately, Bartscher says, this is one subject where he doesn’t have to struggle to get an audience’s attention. When they hear about trafficking, their hearts are moved.

“People want to be involved in this issue,” he says. “They care about these children and adults who are being manipulated. They want to know what they can do to help.”

Scott Craig has seen the same thing over and over, including at Sturgis. “Ninety-nine out of 100 people that you stop at the rally, when you tell them, ‘Here’s a girl we believe is being trafficked here,’ they are aghast,” he says. “They’re disgusted. They take the cards, and we increase our eyes on the lookout a thousandfold.”

All those helpers will be needed again this August, when Sturgis is expected to draw more than a million people for the rally’s 75th anniversary. “That’s great for the economy,” Bartscher says, “but it means we need more boots on the ground.”

As FHA and its allies strive to stop trafficking, they haven’t lost sight of the broader cultural struggle, in which they’re also engaged every day: The fight against an increasingly pornographic culture that feeds increasingly twisted desires.

“There’s got to be an outcry from the healthy, moral public that says, ‘No more!’ ” Craig says. “Pornography is destroying our families, our marriages, our girls. It is causing this epidemic of human trafficking.

“We need to somehow shake the nation by the shoulders and say, ‘Do you not see how we are all guilty of creating this—how we have entertained ourselves for hours on end with sexual and violent programming until we’re desensitized to what we see around us in real life?’ It’s how these girls have become invisible. We’ve lost the ability to see the potential victims.”

Franzen—who recently took a new position as F.R.E.E.’s policy director—sounds a similar note.

“I’m a big-picture person, and I look to understand the cultural climate that lets this happen,” she says. “It’s the failure to value people as the unique creations of God that they are. We have a culture that has largely abandoned the truth of God, and that helps give birth to human trafficking.”

Fighting both trafficking and the larger culture is a big job. But Bartscher—who has been a pastor throughout his adult life—has no trouble staying motivated.

“I’ve always felt that a pastor must speak truth both within the four walls of the church and beyond those walls, in society,” he says. “This statement from Martin Luther King drives me: ‘Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about the things that matter.’ ”

If that wasn’t enough, Bartscher also draws encouragement from another of his heroes.

“On his desk in the Oval Office, Ronald Reagan had a plaque—there’s a replica sitting on mine—that simply read, ‘It Can Be Done.’ That’s what we say about trafficking here. We can turn the tide. And if we can save one child or adult who’s caught in this trap, we know it’s all worth the effort.”

For More Information

To learn more about the Family Heritage Alliance, go to familyheritagealliance.org. To learn about F.R.E.E. International, visit freeinternational.org.