As the old saying goes, truth is often stranger than fiction.

The name Sylvester Graham likely doesn’t mean much to many today, but a reference in a recent book review I read about a new project warning about the dangers of processed food got my attention.

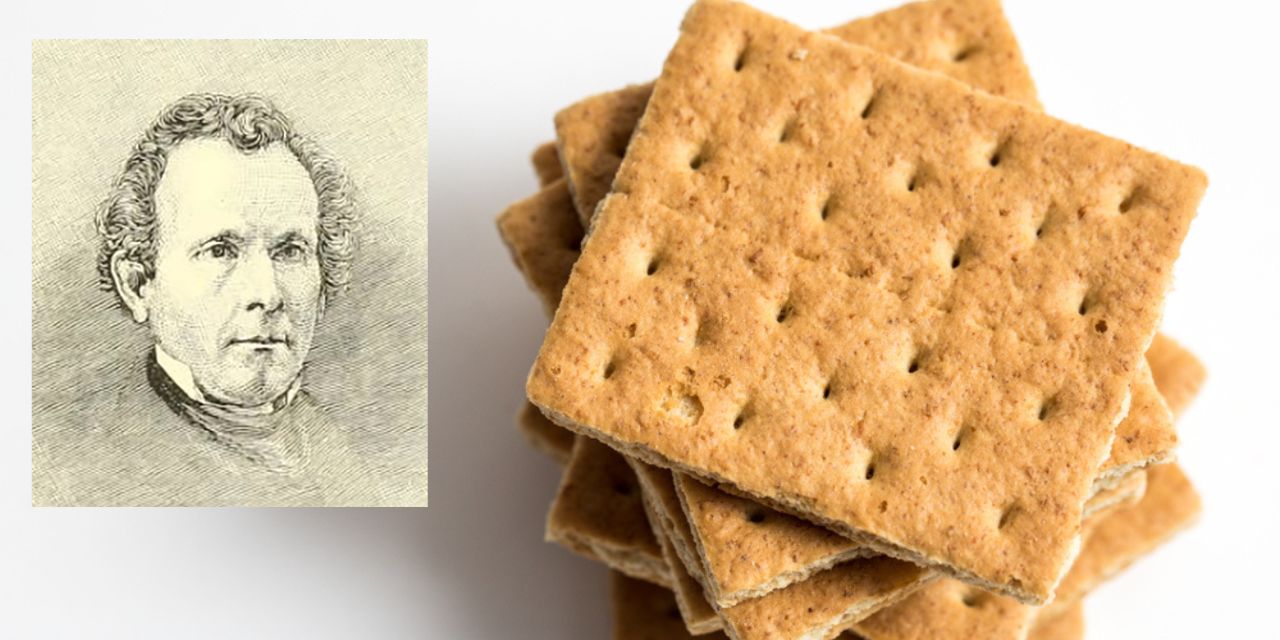

Known for giving us graham crackers, the Reverend Sylvester Graham was born just towards the end of the eighteenth century as the youngest of seventeen children in a northeastern family.

With a mentally unstable mother and a father who died when he was just two, the young Graham bounced between relatives. Living with an uncle who operated a tavern, Graham developed a deep concern for drunkenness and the various vices he saw on display. Convicted and heavy-hearted, he vowed to do what he could do to encourage clean, healthy living.

After a stint at Amherst College, Graham was ordained a Presbyterian minister. But unlike most clergy of his day, he didn’t just preach your typical sermons. Instead, he chose to focus on advocating for sexual discipline and even its connection to good nutrition, including abstaining from meat because Adam and Eve were thought to be vegetarians.

According to reports, the Reverend Graham’s one-two punch was considered so inflammatory and threatening to some that he was more than once literally run out of town. Here’s how the Atlantic chronicled the incident:

He was publicly mobbed in 1834 for attempting to lecture women on the virtues of chastity, and again a few years later by some angry butchers and bakers who considered him bad for business. Nevertheless, Graham flour lined store shelves, and his system of living even inspired the establishment of several male-only boarding houses where Grahamite meals were served and Graham’s precise sleeping, exercise, and bathing regimens were strictly enforced. The Graham Diet went collegiate when Oberlin College adopted it for their dining plan in 1838. Three years later the students protested, one professor was fired over livening up his meal with black pepper, and the diet was rescinded. By the late 1830s, Graham had become too fanatical even for his Grahamites, and his influence began to wane.

The Graham story reminds us, too, that everything old seems to spring new again. The corruption of bread was one of the minister’s gravest concerns. As the popularity of homemade bread began to decline and commercial bread began to rise (no pun intended), Graham took aim at the manufacturers. According to the reverend, the bread was being made with inferior flour, and was even being filled with chemicals and other substances including chalk, clay, and plaster. He was right.

Essays on the eccentric minister play up his other concerns and theories, some of which are a bit offbeat. For example, he believed that sexual desire could be tamed by the consumption of certain foods and regular exercise. The Reverend Graham also advocated for sleeping on hard beds with the windows open in the winter and taking cold baths and showers. Other things he campaigned for that were considered odd then, but normal today, would be the need for drinking plenty of water, getting lots of fresh air and sunshine – and being as physically active as possible.

Sylvester Graham didn’t live to see the commercialization of his cracker, which came about to combat the increasingly unhealthy bread he saw being sold in stores. But the next time you dip one in milk or make a ‘Smore with your children or grandchildren, you might think of him.

Some of the beauty and romance of life is that God has chosen to populate the earth with a wide range of temperaments and personalities, people with all types of gifts and insights designed to work, play and blend together. Sin leaves everyone imperfect and incomplete, so it’s critical for each of us to develop a good sense of discernment. But let’s be careful and cautious about writing people off as crackpots who might be a bit different from us. After all, as our friend Patsy Clairmont liked to say, God uses cracked pots all the time to advance His work and His Kingdom.

Photo from Shutterstock