Legacies matter in the lives of great nations and in the lives of great men. It matters how others regard you. It matters how you treat others. It matters how you have navigated life both in its supreme moments of success and achievement as well as in those chapters of disappointment, failure, and loss.

In this month of August, we will soon observe an important chapter in the life of one of the most consequential American statesmen of the 20th and 21st centuries.

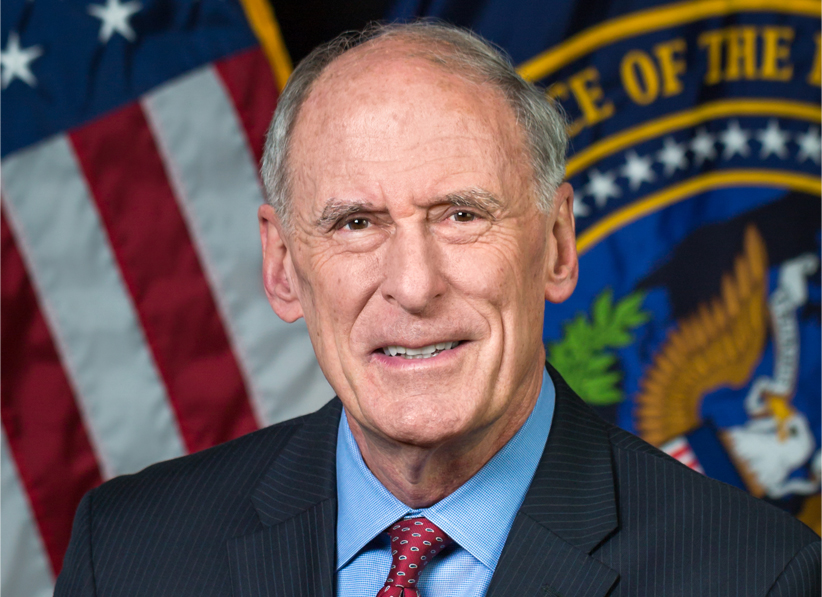

Retiring Director of National Intelligence Dan Coats has now seamlessly joined that rarified strata of having crossed over that invisible divide in American public life that distinguishes a statesman from a politician. There is no award or certificate for when this happens. In fact, it doesn’t happen in a moment or in a vacuum. It happens incrementally through big and small decisions across a lifetime of consequential public service, and it results in being widely and broadly esteemed, even highly-regarded, not only by those who share your same world view but also by those who do not. Each side comes to conclude that the statesman has the best interest of the nation in his heart and soul, and without partisan preference.

In our new book American Restoration: How Faith, Family, And Personal Sacrifice Can Heal Our Nation (Regnery, 2019), my coauthor Craig Osten and I in our chapter “Restoring The Idea Of A Gentlemen” make the case that if we are to renew and regenerate our country and our culture, a significant part of the way forward will be how we form and shape the rising generation of young boys and men into gentlemen. That is, men of unquestioned character, integrity, probity, and prudence whose personal honor and moral code is not only worthy of emulation and immutable but also reflecting and echoing the best of the timeless Judeo-Christian ethos and credo.

It has been the blessing of a lifetime to have known and worked for and with Dan Coats whom I first met in the summer of 1986 when he was a relatively obscure congressman from the Fourth District of Indiana. Rep. Jim Banks, a Focus on the Family alum, now serves in that seat.

I interned for Dan in the House of Representatives in that final year of the Reagan presidency after having interned the previous summer of 1985 in the United States Senate for one of then-Rep. Coats’ best friends, Dan Quayle, who was also from Indiana and who was one of the youngest senators then serving along with the likes of Barry Goldwater, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Bob Dole, and John Stennis – all legendary figures in the history of the senate and all of whom had been in Congress for what seemed like forever.

Interns have a special and unique perch for the observation of members of Congress. They see up-close how they treat members of their own staff, often under the most pressure-filled circumstances. They distinguish how they interact with a group of constituents vs. people who work for them. And interns observe those little but consequential moments – conversations in hallways and elevators with senior staff or other members of Congress as a point of negotiation is ongoing, or with others serving long-years and long-hours who sometimes feel at the breaking point. These various moments give a fuller, wider purview, window, and insight into that representative’s true character and moral courage.

I came to conclude that the public Dan Coats and the private Dan Coats were one and the same man — which is a great rarity in Washington DC.

I came to see that what I observed that summer was borne-out on a larger national stage for years to come — that precisely what people of goodwill pray for in the vocations of their public servants was summed up in the integrity and personal commitment of Dan Coats: wisdom, courtesy, humility, generosity of spirit, good humor, respect for the opinions of those who hold different views, prudence, and above all a genuine, deep, and abiding faith which consistently evidenced itself in a recurring character trait that was one of his most appealing and lasting: asking again and again of others: “What do you think? What is your opinion? Tell me what you believe?” — and then actually listening and absorbing the views of others. How refreshing; how nourishing; how rare.

Two summers after that internship, I went to work for Coats when he moved from the House to the Senate — taking Dan Quayle’s place when Quayle went from the senate to the vice presidency and the White House under George H.W. Bush.

I worked for Coats as his deputy press secretary, press secretary, and communications manager for the next decade. In dog-years, that is about a million years because the average staff turnover in the senate is high. The long days and pressures can take a toll.

I have often been asked: Why did you remain working in the Senate for so many years? I always answered the same way: To work alongside a man of Coats’ caliber and faith was one of the greatest blessings and professional journeys of a lifetime. We shared then and now a world view rooted in our love of Jesus Christ. Coats modeled with humility how to navigate the public square not as a cultural warrior but as a happy warrior. That difference is huge, and he set the pace and hit the high water mark. I learned so much from him, and I owe him so much.

The causes of human life and religious liberty have rarely had a better friend on Capitol Hill than they have had in Coats. He steadfastly defended life and conscience through some of the most important House and Senate debates and votes in the 90s and early 2000s. He embodies everything Focus on the Family stands for in both public service and public policy. If Dan Coats is not a good man, then there are no good men.

All told, he served in the House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate for 24 years; as Ambassador to Germany during the George W. Bush presidency; and until August 15, as Director of National Intelligence. On that day, he will stand down and step out of public life at age 76. For some, that would be among the hardest days of life. For Dan Coats, it will be the next step on what has proven a providential journey of public service that has taken him across the country and across the globe in consistently excellent service to our great nation.

In this, Dan Coats is perhaps the most consequential statesman in the history of the State of Indiana, having had one of the storied careers of public service spanning both the latter part of the 20th and early part of the 21st centuries.

Many are joining in the celebration of Coats’ public service and his common decency.

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) had this to say: “My friend and former colleague Dan Coats has devoted decades of his life in service to our country. I was reassured knowing that a man who took such deliberate, thoughtful, and unbiased approach was at the helm of our intelligence community.”

And from Washington Post columnist Mike Gerson: “Coats is proof that a successful public figure can also be an uncommonly decent man.”

Yet more important than his public service has been a long and happy marriage to Marsha, whom he met at Wheaton College; their three children; numerous grandchildren; and a bevy of deep and abiding friendships that are the summation of the life well-lived.

My friend and New York Times columnist David Brooks has invaluably observed that there are those busy-as-a-beaver folks who spend a lifetime building what he calls ”the resume virtues” while sadly neglecting the far more important ”eulogy virtues.“ The former define your work-life; the latter define who you actually are and your priorities.

Dan Coats is a long way from anyone reciting eulogy virtues; great chapters are yet to come in his and his family’s life. Yet it is fair to conclude that this statesman-gentleman’s legacy of personal sacrifice, underscored by goodwill and gratitude, is enormous.

When one drives onto the campus at Coats’ alma mater Wheaton College in the western Chicago suburbs, you pass a large, beautiful piece of granite or limestone that simply and boldly sets out the credo of that great school: “For Christ and His kingdom.” One of Wheaton’s most famous alums has met that challenge, and then some, and he has done so with humility, humanity, and the grace of Our Lord Jesus Christ. One man’s good life touches many other lives.