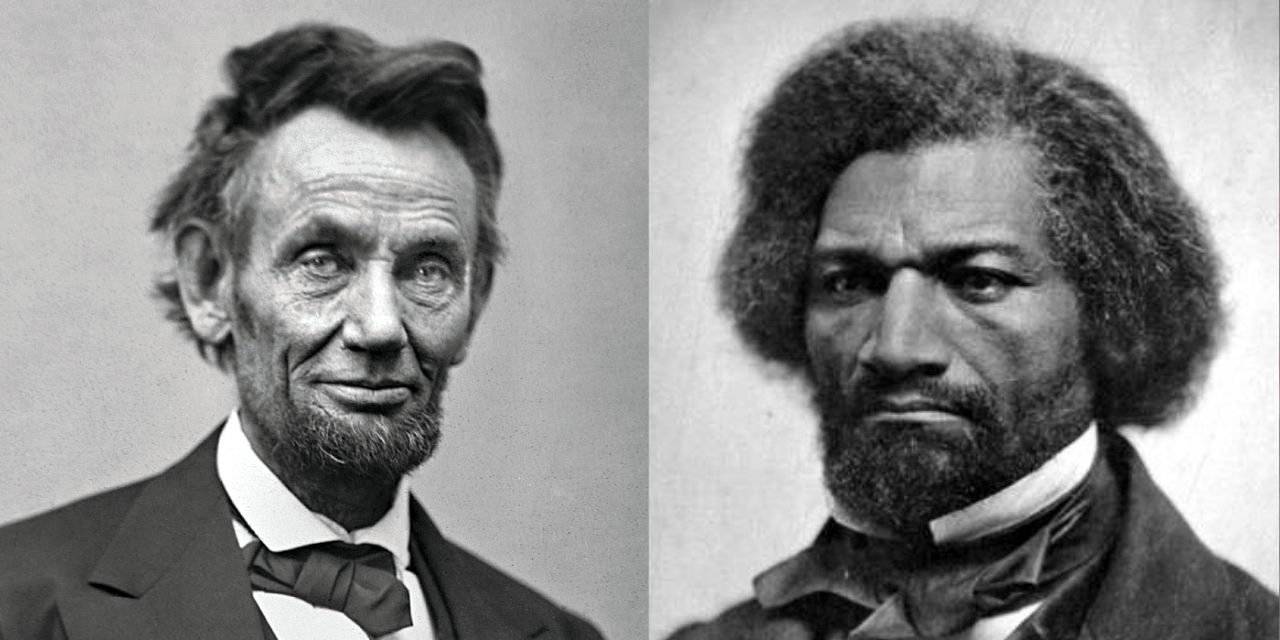

To celebrate Presidents’ Day and Black History Month, The Daily Citizen is providing this detailed story of the warm and interesting friendship between Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass in their own words.

The two men came from extremely modest means, one much more so than the other. But they both went on to a life of remarkable celebrity, accomplishing extraordinary things for our nation. And primarily because each of them understood the rare power of self-education and the gift of books. One was born in a humble one-room cabin in the South. The other was born into southern slavery in Maryland. They would both become two of our nation’s greatest and most consequential, but dramatically different, leaders during our nation’s most trying time.

Frederick Douglass taught himself how to read, recognizing in his earliest years that education could be “the pathway from slavery to freedom.” He escaped that slavery in Maryland at the age of 20, landing as a free man in New York City in 1838 via stops along the Underground Railroad. Douglass was a man of great ambition and possessed a moral conviction of steel. He published the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass: An American Slave in 1845 and began his own antislavery newspaper, The North Star, just two years later. Within years of winning his freedom, Douglass became the most famous African-American man in the country.

In the Presidential election of 1860, Douglass publicly endorsed the Republican candidate, as the Democrats were famously pro-slavery. This candidate, of course, was Abraham Lincoln who won office with less than forty percent of the popular vote, but successfully earned the majority of Electoral College votes. Douglass half-heartedly celebrated the would-be Great Emancipator’s victory, writing the month after his election in 1860,

Mr. Lincoln, the Northern Republican candidate, while admitting the right to hold men as slaves in the States already existing, regards such property as peculiar, exceptional, local, generally an evil, and not to be extended beyond the limits of the States where it is established by what is called positive law.

Douglass fell short of calling Lincoln “an Abolition President.” In fact, he referred to the new President rhetorically as “the Abolition movement[’s] …most powerful enemy,” because of his resistance to dissolving the Union. But Douglass asked his readers to ponder this larger question for the longer cause,

What, then, has been gained to the anti-slavery cause by the election of Mr. Lincoln? Not much, in itself considered, but very much when viewed in the light of its relations and bearings.

Douglass explained that for 50 years, the “haughty and imperious slave oligarchy” have been the “masters of the Republic,” their authority “almost undisputed.” But Douglass recognized this was no longer the case. In his essay entitled “The Late Election,” Douglass expressed at length his expectation from this unexpected electoral outcome,

Lincoln’s election has vitiated their authority, and broken their power. It has taught the North its strength, and shown the South its weakness. More important still, it has demonstrated the possibility of electing, if not an Abolitionist, at least an anti-slavery reputation to the Presidency of the United States. The years are few since it was thought possible that the Northern people could be wrought up to the exercise of such startling courage.

Hitherto the threat of disunion has been as potent over the politicians of the North, as the cat-o’-nine-tails is over the backs of the slaves. Mr. Lincoln’s election breaks this enchantment, dispels this terrible nightmare, and awakes the nation to the consciousness of new powers, and the possibility of a higher destiny than the perpetual bondage to an ignoble fear.

Lincoln’s moral outrage toward to the institution of slavery itself was evident. But he was the also the President of the nation and his desire to hold the Union together was paramount. Of course, the Civil War began just months into his presidency on April 12, 1861. Lincoln’s position and responsibility as the nation’s leader brought difficulty to Mr. Douglass. The two men did not have the luxury of addressing the issue of slavery with the same concerns and convictions. They respected one another, but also found themselves separated by significant conflict in practicality over such questions as “How could slavery end?” and “What would become of the freed slaves in their post-slave lives?”

But Douglass publicly celebrated his friend with these poetic words of October 1862 in an essay entitled “Emancipation Proclaimed” in Douglass’ Monthly,

Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, Commander-in-Chief of the army and navy, in his own peculiar, cautious, forbearing and hesitating way, slow, but we hope sure, has while the loyal heart was near breaking with despair, proclaimed and declared:

“That on the First of January, in the Year of Our Lord One Thousand, Eight Hundred and Sixty-three, All Persons Held as Slaves Within Any State or Any Designated Part of a State, The People Whereof Shall Then be in Rebellion Against the United States, Shall be Thenceforward and Forever Free.”

“Free forever”

Oh! long enslaved millions, whose cries have so vexed the air and sky, suffer on a few more days in sorrow, the hour of your deliverance draws nigh!

Oh! Ye millions of free and loyal men who have earnestly sought to free your bleeding country from the dreadful ravages of revolution and anarchy, lift up now your voices with joy and thanksgiving for with freedom to the slave will come peace and safety to your country.

Douglass gave a famous, national call recruiting “Men of Color, To Arms!” which was published in The New York Times, advocating for equal pay and treatment for all Union soldiers. He even persuaded his own sons, Charles and Lewis, to join the Fifty-Fourth Massachusetts Infantry Regiment.

On August 10, 1863, Douglass paid his tall friend a visit at the White House to make sure he understood the mistreatments suffered by Black soldiers in the battle to preserve the Union. The President gave him permission to start a campaign recruiting both Black and White soldiers from the South.

A year later, the two men met again at the White House, as Douglass recounts in his final autobiography, The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, From 1817 to 1882.

What he said on this day showed a deeper moral conviction against slavery than I had even seen before in anything spoken or written by him. I listened with the deepest interest and profoundest satisfaction, and at his suggestion, agreed to undertake the organizing a band of scouts, composed of coloured men, whose business should be somewhat after the original plan of John Brown, to go into the rebel States, beyond the lines of our armies, and carry the news of emancipation, and urge the slaves to come within our boundaries.

This plan, Douglass explained, was finally unnecessary because of the ultimate emancipation of the slaves. But he adds, “I refer to this conversation because I think it is evidence conclusive on Mr. Lincoln’s part that the proclamation, so far as least as he was concerned, was not effected merely as a ‘necessity’” but as a moral duty.

Douglass traveled to Washington D.C. to hear the President give his second inaugural address in 1865. He accepted the President’s kind invitation to visit him and his family at the White House, even though the doorkeepers hindered his entrance for a time, noting only his skin color, rather than the distinctive and noble visage of the great man. Once cleared, Douglass recalled their special meeting in his Life and Times,

Recognising me, even before I reached him, he exclaimed, so that all around could hear him, “Here comes my friend Douglass.” Taking me by the hand, he said, “I am glad to see you. I saw you in the crowd to-day, listening to my inaugural address; how did you like it?”

I said, “Mr. Lincoln, I must not detain you with my poor opinion, when there are thousands waiting to shake hands with you.”

“No, no,” he said, “you must stop a little, Douglass; there is no man in the country whose opinion I value more than yours. I want to know what you think of it?”

I replied, “Mr. Lincoln, that was a sacred effort.”

“I am glad you liked it!” he said, and I passed on, feeling that any man, however distinguished, might well regard himself honoured by such expressions, from such a man.

An escaped slave and the President of the greatest nation on earth talking in the White House as trusted and cherished friends. The latter telling the former, even as he was almost prohibited from entering that evening, that he is the most esteemed and trusted man in the nation.

When the great President was killed less than two month later by an assassin’s bullet, the first lady gave Douglass her husband’s honored and “favorite walking staff” as a reminder of the great support he had given Lincoln during impossibly trying times. In his thank you note to the President’s stricken widow, Douglass told her “I assure you, that this inestimable memento of his Excellency will be retained in my possession while I live – an object of sacred interest – …an indication of his humane interest in the welfare of my whole race.”

Such was the deep regard between two equally great, but unlikely friends.