The United States presidential election has come down to what we don’t yet know, and as Tom Petty famously said, “The waiting is the hardest part.”

So, how will our true, actual presidential decision be made in 2020?

Will the networks call it? Our nation’s leading newspapers? The New York Times boldly claimed this very thing Tuesday evening in a now wisely deleted tweet. Or will it be determined by our candidates’ blustery assertions? How will we really know when and who the actual, legal President of the United States is? That seems to be the question on everyone’s mind at present.

Who Truly Calls the Election?

Well, we do know this, and it is very good news. Even though this seems to be an unprecedented Presidential election, the constitutional process for how we elect our executive leader remains the same and is clearly explained here by the national archive and in this official simple infographic from the United States government. We are, and we remain, a nation of careful, deliberative order and law.

In reality, our process for electing a president is not one event, but two. We are literally in the process of completing the first part, casting and certifying the legal votes of the American people. They have been cast. They are now being counted and certified by our state officials.

The second part of this process is completed by the constitutionally established Electoral College which meets later in December and cast their ballots for President and Vice President, based on our individual votes. This year, their meeting and voting date is December 14, 2020. A president will not and cannot be officially determined before that date by anyone other than the 538 electors of the Electoral College.

This process was established by Article II, Section 1, Clause 2 of the U.S. Constitution and modified by the 12th and 23rd Amendments.

Why an Electoral College?

Our nation’s founders determined that we would ultimately elect our President every four years through the Electoral College, rather than by straight popular vote. They did this for extremely important reasons that have everything to do with maintaining a true and equal representational government. Our wise founders appreciated that a minority +1 can easily control and dominate the other minority which is no way to run a thriving representative democracy. So they developed the Electoral College to protect minorities. And yes, the Electoral College makes the process more complicated, but that was our Founders’ precise intention because it wisely protects against the tyranny of the minority +1. Our nation never would have made it to 2020 without it.

So after the citizens cast their individual Presidential ballots, which happen the first Tuesday in November every fourth year, the second phase of our Constitutional election takes place in mid-December when the nation’s 538 Electoral College electors casts their ballots based on each state’s citizens’ votes. It is these 270 votes by the electors, and only this vote, that officially determines the new President of the United States of America. This is explained nicely in this Prager U video.

So, the next President of the United States will be officially determined, according to our careful and deliberative Constitutional routine, December 14, 2020. From there, the process to inauguration proceeds as,

- Senate Deadline for Receipt of Ballots – Dec. 23, 2020: The electors’ ballots from each state and district must be received by the president of the U.S. Senate by this date.

- Congress Counts the Electoral Ballots – Jan. 6, 2021: The U.S. Congress meets in joint session to count and certify the electoral votes.

- Inauguration Day – January 20, 2021: The president-elect becomes the president of the United States.

When the Vote is Too Close?

When the results of the popular vote are extremely close and contested, like they are this year and have been in many other election years in our nation’s great history, the electoral college has a deadline for when those disputes must be determined and resolved. These disputes have been very bitter over the long decades of our nation. What is unique in this election year are the effects that COVID-19 lockdowns have had on how our votes are cast and recorded.

This year, that deadline for resolving all election disputes at the state level is December 8, 2020. Thus, there is no real problem or constitutional crisis with the final determination of vote count being made until that time. Our normal process allows for this. As the National Conference for State Legislators explains,

An election isn’t over when the polls close. It’s over when election administrators complete their postelection activities and the election results are certified. As with everything else related to elections, state law governs these postelection processes—and there are 51 models. (The states plus Washington, D.C.).

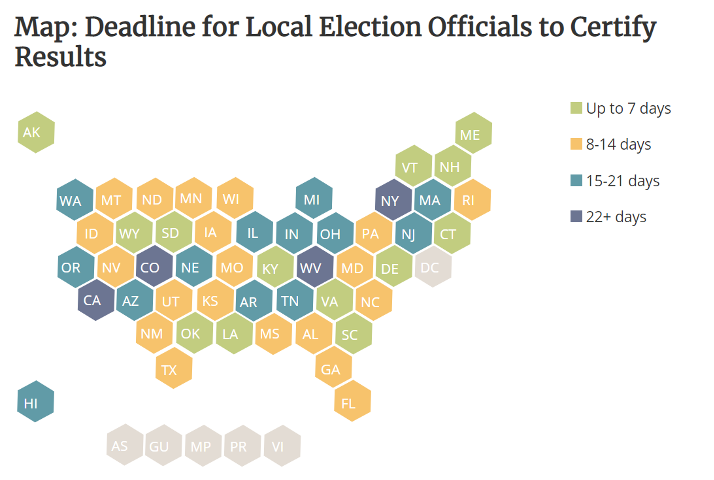

This is where the process currently sits, with the 50 states and the District of Columbia counting and certifying their votes. This curiously means that things are right on track, even if they seem otherwise. You can see how many days your state or district has to certify its own vote from Tuesday in this graph.

Credit: National Conference of State Legislatures

Of course, lawyers get deeply involved in this certification process, doing their best to make sure that the counts at the state and district level are fair and proper for their candidate. The courts are the authority who oversee and decide the disputes brought by either campaign’s lawyers. These disputes can make their way all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court as they have two times before. It is therefore fortunate that our nation now has a complete, rather than equally divided, Supreme Court with the official seating of Justice Amy Comey Barrett in late October.

Faithless Electors in the Electoral College

The official electors who make up the Electoral College are otherwise ordinary citizens who have been colorfully described as “538 party-selected, faceless robots.” These are people selected and pledged to vote for the candidate who officially won their states’ popular vote. If there is an Electoral College tie, like there was in 1824 and 1876, the House of Representatives would elect the President with 26 votes and the Senate would elect the Vice President with 51 votes.

Another problem that can take place in the Electoral College is what is termed “faithless electors” or electors who chose to break their pledge and vote contrary to what their state’s citizens wanted. This has happened 156 times in our nation’s history, but faithless electors have never changed an election’s outcome.

Thirty-three states (plus the District of Columbia) have laws requiring their electors to vote for a pledged candidate. However, 16 of these states including DC do not provide for any penalty against faithless electors. Only five states provide for some penalty for a deviant vote by a faithless elector, and 14 states provide for the vote to be canceled and the faithless elector replaced by a faithful one. The Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of these laws in Chiafalo v. Washington on July 6 of this year.

So, citizens, rest assured, we have a long and tumultuous way to go in determining who our next president is. But as of now, even with all the confusion, our constitutional process is right on track and we should pray for the honesty and integrity of our civic leaders and trust in the wisdom of the process our Founding Fathers laid out for us.

Photo from M Ainuha Zainur R / Shutterstock.com

Visit our Election 2020 page