Last week, in another attempt to erase America’s history and heritage, radical activists attempted to bring down the statue of former President Andrew Jackson that stands across the street from the White House.

Whether we agree or disagree about the legacy of our seventh president, it is time for us, as Americans, to unite around and promote the legacy of those whose lives affirmed the concept of Imago Dei – that we are all created in the image of God and thus are to be treated with dignity and respect – rather than simply tear down and destroy tributes because we may not agree with the policies or actions of assorted historical figures.

One such person, a man who brought people together rather than tore them part, and who thus far only has a statue in the Emancipation Hall in the U.S. Capitol Visitors’ Center, is Frederick Douglass who worked tirelessly and dedicated his life to the cause that all individuals would be free.

Douglass was born to a female African American slave and an unidentified white father in Talbot County, Maryland in 1818. For the first two decades of his life, he was treated like a piece of property to be traded back and forth by various masters. But Douglass was fortunate to learn how to read and write by a white woman who taught him the alphabet. That ability opened up Douglass’s eyes, as he learned more about slavery from various books and other publications, and quickly became an advocate to help free and advocate for his fellow brothers and sisters trapped in its bondage. In addition, he was able to successfully escape slavery himself, reaching New York, a free state.

It was in New York that Douglass became a fervent speaker at anti-slavery meetings, as well as the author and publisher of the “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass,” which documented his successful escape. The book became a best seller and his notoriety put himself in danger of capture and return to his former owner. But Douglass would not be deterred. He persevered. He traveled to Great Britain and Ireland and was able to raise enough money to purchase his release from slavery. He returned to New York, where he was an advocate of woman’s rights, sheltered slaves seeking to escape, and led the battle to stop racial segregation in public schools.

Douglass became an advisor on race issues to two presidents: Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant – whose statues have been recently targeted by individuals such as those who sought to topple Andrew Jackson. Instead of attacking these two men, which is often the modus operandi of activists today, he sought to build an alliance with them in order to achieve a common goal of a day when all individuals would be free.

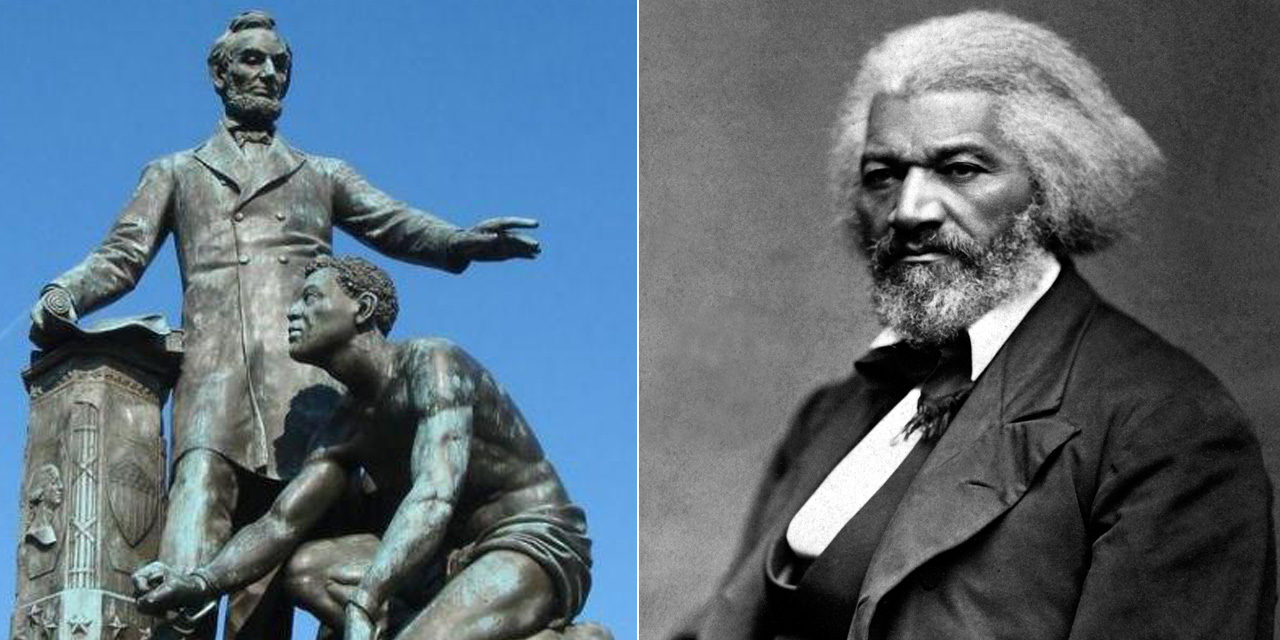

During the Civil War, Douglass served as a recruiter for the first African American army regiment. Two of his sons would join that regiment. In his meetings with President Lincoln, he shared his views on the pay and treatment of African American soldiers and discussed the president’s wishes to help escaped slaves. While Douglass may have been privately frustrated that Lincoln did not move fast enough in his view on the emancipation of the slaves, he never let that frustration stand in the way of working with the president towards their common goal. At the dedication of a statue of Emancipation Memorial in Washington, D.C.’s Lincoln Park – a statue now being targeted for removal, because it depicts Lincoln holding the Emancipation Proclamation while freeing an African American slave – Douglass said:

“The name of Abraham Lincoln was near and dear to our hearts in the darkest and most perilous hours of the Republic … We saw him, measured him, and estimated him; not by stray utterances to injudicious and tedious delegations, who often tried his patience; not by isolated facts torn from their connection; not by any partial and imperfect glimpses, caught at inopportune moments; but by a broad survey, in the light of the stern logic of great events, and in view of that divinity which shapes our ends, rough hew them how we will, we came to the conclusion that the hour and the man of our redemption had somehow met in the person of Abraham Lincoln.”

These words of Douglass are prophetic for our time as he was a uniter and not a divider. He could have screamed and made demands – like so many do today on social media or on cable television – about his frustration with the pace of the emancipation effort. But instead he sought to change hearts and minds through persuasion rather than violence.

Along with the Emancipation Memorial in Washington, D.C.’s Lincoln Park, a copy of the same statue, located in Boston, has come under similar attack from the same groups seeking to tear down any remnant of America’s past. It would be a great tragedy and travesty if both of these statues, meant to honor Lincoln and to celebrate the end of the scourge of slavery, were to be displaced and destroyed.

Rather than remove the statues of those from our nation’s past, wouldn’t it be better to have a statue of Douglass in a more prominent place than the U.S. Capitol Visitor’s Center? His presence, alongside other American heroes, would remind us all that it is perseverance, persuasion, and building alliances that brings about positive change, rather than division and destruction. Let’s build a statue celebrating his legacy, rather than tear down and destroy our past.

Photos from Wikipedia / Wikipedia

Visit our Election 2020 page