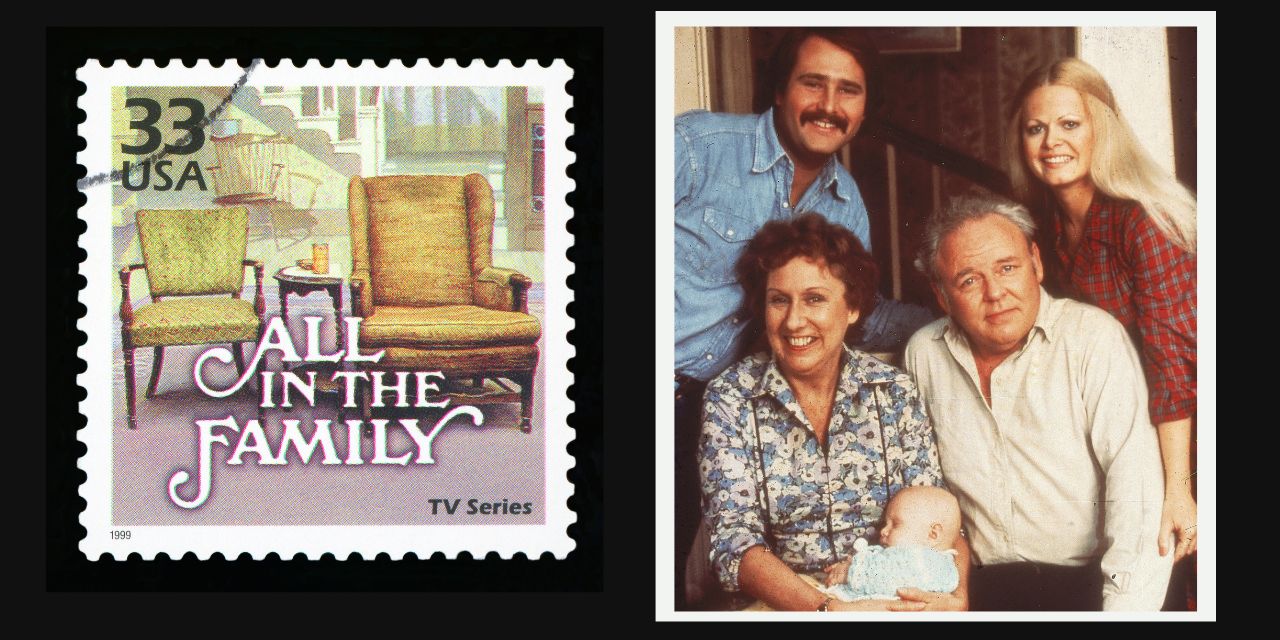

The death on Tuesday of pioneering television writer and producer Norman Lear brings back into the headlines some of the most popular sitcoms of another era, including All in the Family, Maude and The Jeffersons – top-rated programs of the 1970s.

Phil Rosenthal, credited with creating the 1990s sitcom Everybody Loves Raymond, called Lear “the most influential producer in the history of television, because of this gigantic change that happened when All in the Family hit the air.”

What was so gigantic?

Prior to the show’s launch in 1971, television sitcom plotlines were predictable and culturally positive. They didn’t push the envelope morally or challenge long-held family-friendly conventions. By and large, parents could watch television with young ears or eyes in the room and not worry about having to explain adult topics that may or may not be presented fairly or fully.

Yet All in the Family, a program based on a British sitcom (Till Death Do Us Part) with a similar edge, sought to expose stereotypes and publicly expose by shock and awe what Lear believed was widespread prejudice, among other things. The show brought into homes themes and comments otherwise unsaid, or subjects previously deemed inappropriate for family viewing.

Archie Bunker became the face of the ignorant, white bigot who thought he knew almost everything – and who lamented the fact that nearly everyone else, except maybe his buddies, knew next to nothing.

“TV’s new frankness should be seen not only as the product of a laudable spirit of experimentation but nomic realities,” wrote The New York Times’ Daniel Menaker on November 4, 1973.

To be fair, many of the topics and situations addressed in Lear’s culturally explosive shows weren’t entirely imagined or manufactured, but the troubling precedent the Connecticut-born mogul unleashed is difficult to overstate.

Almost overnight, Lear transformed television into a social engineering tool. Unprepared parents and unsuspecting youngsters became the guinea pigs in a grand experiment that contributed to the sexual and cultural revolution that’s still being felt today.

On Lear’s sitcom Maude, viewers were stunned when the lead married couple, played by Bea Arthur and Bill Macy, decided to abort their baby. The outcry was loud and sustained, especially by people of faith. CBS, which aired the show, even objected to the storyline, but ultimately relented and allowed it. The Rubicon had been crossed. Looking back on the controversy, Lear took glee in offending Christians, especially pastor Dr. Jerry Falwell. “How could you not be proud of that?” he told Jimmy Kimmel.

Then there was the dialogue of shows like All in the Family. To quote my fourth-grade teacher, conversation was “Rude, crude, and socially unattractive.” Characters were mean, biting and bitter. The home was a circus. It normalized dysfunction.

Television has long been called a babysitter, but Lear helped leverage it to become a political and social propaganda juggernaut. Consider how powerful and influential hours and hours of liberal talking points can be masked as so-called entertainment.

Of course, Lear wasn’t the only one taking advantage of the seismic shift – but he was one of the first and most prolific. That said, social and religious conservatives don’t escape blame either. Whether watching it or going along to get along, many of the topics Lear raised and addressed should have been subjects addressed in the pulpit or in homes by mothers and fathers committed to educating children and living up to their responsibility as parents to tackle social sins that regularly confound mankind.

People of faith are often guilty of sins of omission, and that’s what happened here.

Norman Lear saw an opening and exploited the void. By acquiescing to Hollywood, generations have been brainwashed and duped into thinking what Norman Lear wanted them to believe about a wide range of issues.

Images from Shutterstock and Getty.