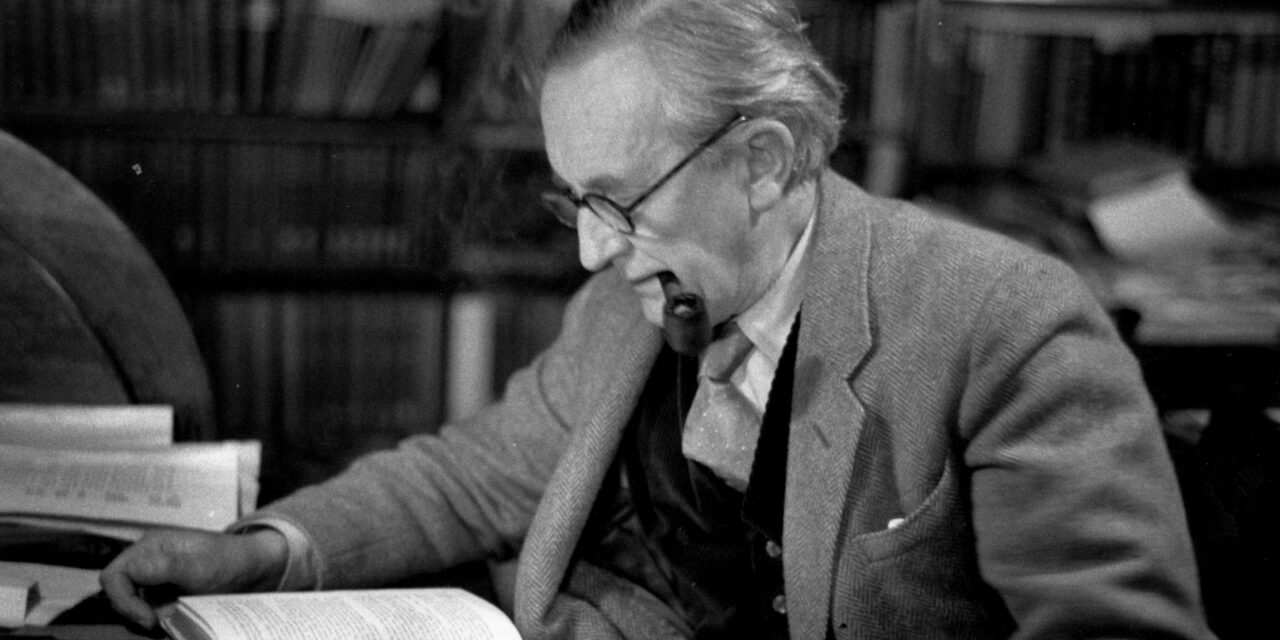

Fifty years ago on September 2, one of the most important authors of the twentieth century passed away. While most today know his amazing works of fantasy and fiction, J.R.R. Tolkien was long recognized in academic circles as a brilliant philologist and scholar of medieval literature. For example, his essay on Beowulf, written in 1936, reshaped scholarship around the poem and remains highly influential today.

It was in the following year that the world was first introduced to Middle Earth. The Hobbit was quickly recognized as a wonderful children’s book. But The Lord of the Rings series that followed initially earned a mixed reception. C.S. Lewis and W.H. Auden, among others, quickly saw its genius, but many critics dismissed it as an overblown fairy tale, a contribution to a literary genre out of favor among modernist critics who favored “realistic” literature that dealt with the angst of the mid-twentieth century. Tolkien, however, believed that the world, and Britain in particular, needed something else.

Over the last few decades, Tolkien studies have blossomed into an important field. His popularity soared with Peter Jackson’s film adaptation of The Lord of the Rings, and more significantly, people have been exploring the philosophical ideas behind Tolkien’s legendarium. The full scope of Tolkien’s vision has been made available thanks to the indefatigable work of his son Christopher, who analyzed and edited the many manuscripts Tolkien left behind. We now have a fuller picture of his writing process and the creative vision behind Middle Earth, as well as the intellectual influences that informed Tolkien.

Some of these influences are well known, including Beowulf and Norse and Germanic mythology. A linguist, Tolkien invented entire languages based on Finnish and Welsh, as well as several writing systems to go along with them. A philologist, he studied language as a window into culture, which led him to develop both history and culture to go with his newly invented languages. From this effort came the amazing world of Middle Earth.

Tolkien also drew on his own life story in crafting his stories. His description of the Dead Marshes and Mordor were inspired by his experience in the trenches in World War I. Also, Sam and Frodo’s relationship was based on Tolkien’s experience as an officer with his batman, an enlisted man who served as a personal assistant.

As a boy, Tolkien spent several years in the Birmingham area where he grew to love the English countryside and to hate industrialization. This obviously shaped his descriptions of the Shire and the ecological concerns in the legendarium. On a literary level, this connected him with British romanticism, a movement that emphasized beauty, imagination, and God. In fact, as Austin Freeman pointed out in a recent interview on the Upstream podcast, Tolkien explained that to understand his writing, one had to remember he was a British romantic and a Christian.

The significance of Christianity to Middle Earth is a matter of some controversy. Tolkien himself wrote, “‘The Lord of the Rings’ is of course a fundamentally religious and Catholic work.” Critics have scoffed at this, pointing out that there is little hint of religious practice in The Lord of the Rings nor any of the distinctive doctrines of Christianity. In some Tolkien fandoms, discussion of Tolkien’s faith is forbidden, as if his work can be understood apart from the author.

However, there are clear Christian influences on the story, even if not intentional. When someone pointed out that the three offices of Christ—prophet, priest, and king—were embodied by Gandalf, Frodo, and Aragorn, Tolkien responded that though it was not intentional, his Christian beliefs would inevitably come out in his writing.

More recent scholarship, such as Bradley Birzer’s J.R.R. Tolkien’s Sanctifying Myth, has revealed the profound Christian ideas at the root of Tolkien’s work. Jonathan McIntosh’s The Flame Imperishable argues that Tolkien’s creation myth was shaped by the metaphysical ideas of Thomas Aquinas. Austin Freeman’s Tolkien Dogmatics looks at Middle Earth through the lens of systematic theology and identifies important elements of Christian belief embodied there.

Tolkien, of course, was never preachy, which is why his Christianity is so easily and often missed. However, as he explained in a letter, “[The] religious element is absorbed into the story and symbolism.” Still, Tolkien’s stories speak to profound truths about the world, and thus, can, in C.S. Lewis’s words, “steal past those watchful dragons” of modernity.

This Breakpoint was co-authored by Dr. Glenn Sunshine. For more resources to live like a Christian in this cultural moment, go to breakpoint.org.

Photo from Getty.