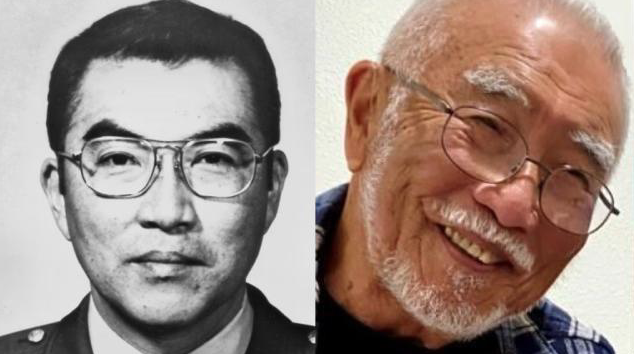

You may have never heard of Brigadier General Theodore “Ted” Shigeru Kanamine – a highly decorated Army officer, and the first Japanese-American general in the Army who served America admirably for 27 years, including stints in Korea and Vietnam.

General Kanamine died last week at the age of 93.

Ted’s life is a story of loss and disappointment. It’s also a story of redemption and a lesson in forgiveness. It’s a reminder that most of life isn’t what happens to us – but how we react to what happens to us.

There were two halves to Ted Kanamine’s childhood. The first was idyllic. He was born in Hollywood, just a block away from the Walt Disney Studios. The year was 1929. And living in Hollywood so close to the capital of entertainment had its perks, especially as a young kid.

Ted remembered Walt Disney coming into his parents’ food market. They became friends and the neighborhood children flocked to the rising creator. In fact, Walt wound up inviting Ted and his friends down to the studio on Saturday mornings to watch a sneak preview of the newest movies and cartoons.

“We’d gather into the viewing room and sit on the floor,” Ted remembered. “All the executives and artists and cartoonists were sitting behind us. They would show these unfinished cartoons that hadn’t been colored in yet.”

But then came Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, and everything changed dramatically for the Kanamine family and nearly 120,000 other Americans of Japanese ancestry living in the United States. There would be no more Saturday morning cartoons for the kids at the Disney Studio. In fact, there would be no more family market. President Roosevelt ordered all those of Japanese heritage to be rounded up and imprisoned.

Back in 1988, President Reagan signed legislation formerly apologizing for the decision, and provided a restitution payment to the 60,000 Japanese-Americans still living.

“Yes, the nation was then at war, struggling for its survival, and it’s not for us today to pass judgment upon those who may have made mistakes while engaged in that great struggle,” Mr. Reagan said at the time. “Yet we must recognize that the internment of Japanese-Americans was just that: a mistake.”

The Kanamines were forced to sell their store and nearly all their possessions. Their lives were reduced down to two bags each. They were first shipped over to the Santa Anita Racetrack for several months, and then Ted and his family were relocated to a camp in Arkansas.

In his Washington Post obituary, General Kanamine is quoted as saying, “There was always an anxiety to get out of there. We were behind barbed wire and there were guard towers, so it wasn’t just a matter of walking out.”

The Kanamines were allowed to walk out after the war was over. Thankfully, the government had the foresight to create another relocation program, and the Kanamines tried to get back on their feet by moving in with a well-off family in Omaha, Nebraska. Ted finished high school, went to college, and then joined the Army as an officer through the ROTC program.

At the time, the US was wrapping up the Korean War and preparing for Vietnam. The newly minted officer would get married, have four children, and begin climbing the ladder with promotions and new assignments. The family moved twenty-one times.

General Kanamine’s greatest military struggle came in Vietnam, where he was under almost constant fire. For his bravery and valor, he was awarded, among other citations, the Distinguished Service Medal, two awards of the Legion of Merit, the Bronze Star Medal and two awards of the Meritorious Service Medal.

“War is no fun,” he once said. “We must do all that we can to avoid war. But if war is the only choice, we must win!”

General Kanamine was also tasked with investigating abuses of military power in Vietnam, which he did soberly and judiciously.

How do you travel such a road without generating and harboring resentment?

Linda Kanamine, Ted’s daughter, said, “He never complained. He never disparaged his country or the government. He just became the most patriotic human being you could imagine.” Through all the challenges, Ted maintained an even keel.

But General Kanamine didn’t overcome obstacles by pure grit and gumption alone. He was a strong believer, and he leaned heavily on faith, embracing the wisdom of Hebrews, which urges:

“See to it that no one fails to obtain the grace of God; that no ‘root of bitterness’ springs up and causes trouble, and by it many become defiled” (Hebrews 12:15).

Ted led a men’s group at his church, and was also instrumental in the building of his parish, Holy Family Catholic Church in Port St. Lucie, Fla. He also served as Disaster Chairman for the Red Cross.

“It’s not just what you eat that matters, it’s what eats you,” said pastor Rick Warren. “You can have all the right macrobiotics and organic food, but if your body is filled with resentment, worry, fear, lust, guilt, anger, bitterness, or any other emotional disease, it’s going to shorten your life.”

“Life is not always ‘peaches and cream,’” said the general. “Tough times and big problems arise but a close family and good friends can solve almost anything. Home and country must be protected. Have the personal discipline to know what is right and develop the skills necessary to do whatever the task is in the best way you know how.”

General Kanamine’s willingness and ability to forgive and let go of any bitterness he may have had about his family being imprisoned made the happiness and success of his life possible.